Echoes

It is week two of the Coronavirus shutdown, and I’ve driven away from home for a bit to get some solitary space. I’m parked in Oak Grove Cemetery in La Crosse, having just finished meditating in the seat of my car. It was a good session; and despite the pandemic—with the attendant fear, precautions, and social distancing, I am feeling alright. I have the windows cracked to let in the cool air. The sky is brilliant blue, and the sun warms my face. I hear the songs of birds. It is March 21, 2020—two days into the spring season. In this precise moment, everything in my immediate world is fine. Strangely, anxiety has not taken over my life, as it surely would have in the past.

Grandpa and Grandma Brown’s graves are within sight. Uncle Raymond’s is just next to theirs. Ray was the first of our little family to be buried here, in the summer of 1946. Grandpa was next, in 1969, and Grandma joined him here in 1980, at the age of ninety. Aunt Genevieve and Uncle Al Ames lay nearby. They passed in 2004 and 2001. You and Mom are across the entire cemetery, interred in a newer garden mausoleum. All in all, it’s a regular Brown ancestral reunion in the space of a few square blocks.

Oak Grove is one of my more frequent contemplative stopovers, my energy stations. I feel your presence keenly there on some days, as well as Mom’s and those of Grandma and Grandpa. And while I come to Oak Grove generally to meditate, with the goal of achieving a temporary state of limited thought, I also visit it during times of personal trial, when there is no stopping and often no limit to my thinking. These are occasions when I seek succor or direction, or some otherworldly assurance that I am looked over.

Because there are times when we all need our folks. And even though I came to a point where I didn’t ever want to admit it, I truly needed both you and Mom. And as much as I have spent my adult life decrying you both for your habits and temperaments and the awful situations they engendered, I can and must also admit that, more often than not, you were there for me when I needed you most.

Blackbirds hop among the headstones today, pecking about for whatever food the awakening earth can provide them. They’ll be fine, of course. Birds are resilient. They’ve been here throughout the span of human memory. The blackbirds skittering and flying in Pieter Bruegel’s paintings from the sixteenth century are these birds’ relatives. I draw comfort from their presence, their persistence. They are muses, triggering my thoughts on the passage of time. In autumn, during the annual migrations, I look up at those ubiquitous, irregular V’s of honking geese bearing south and know that they are following courses set in their DNA over tens of thousands of years. If anything in the living world better stands out as analogous to the promise of continuity, I don’t know of it. Perhaps the sun rising in the east every morning trumps their example, but that is almost too easy. These birds are flesh and blood. Compared to the sun, their timeline is more finite and relatable, yet still comfortingly vast, reaching back across the epochal vale to their own genetic forebears, the dinosaurs, and then forward too, just as far or (who knows?) possibly even further.

***

The German psychotherapist Bert Hellinger once remarked, “you are the dream of all your ancestors.” What I believe he meant is that, for certain individuals who are willing and able to do the work, it is possible to set in forward motion a process of healing from dysfunctional or destructive patterns that have dogged previous generations of a family. What it takes are the rebels, the “black sheep” in Hellinger’s words, who, whether through direct intention or the sheer impact of their idiosyncratic ways, give life to “new and blooming” branches on a family tree blighted by dysfunction or misdirection. As Hellinger so aptly put it, these family oddballs have the opportunity, if not the duty, to manifest and set right the “countless unfulfilled desires, unfulfilled dreams, frustrated talents” of their ancestors.

I often wonder how things might have turned out had fate intervened differently along our family path at certain junctures. For example, how did the death of Grandpa Brown’s father, George Washington Ingersoll, influence Grandpa’s life course and, arguably, yours and mine as well?

George Ingersoll, the youngest of three siblings, was something of an outlier in his own immediate family. As adults, his older brother and sister both followed the family path of farming in the rolling lands of southeastern Illinois and southwestern Indiana. George, by contrast, was a schoolteacher who hoped eventually to become a lawyer. He was a learned, thoughtful man, respected as an educator, active in politics. He sounds like someone I’d like to sit down with over coffee, and I now wonder whether it’s possible that at least some of my intellectual curiosity might have come down the line from him.

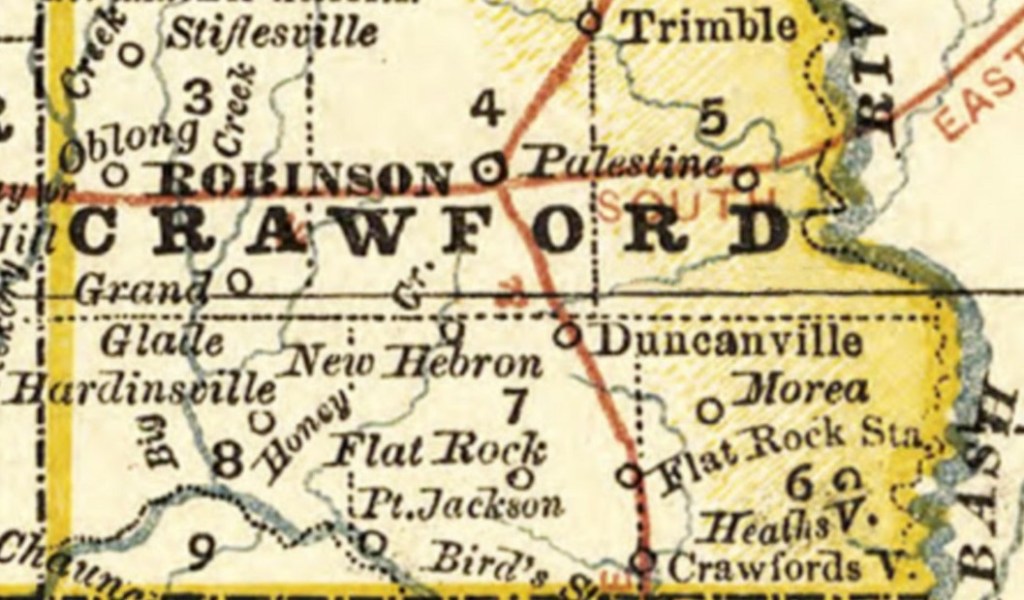

He was a sought-after speaker too. Local newspapers refer to one of his lectures, delivered at a meeting of the Robinson, Illinois Republican Club in 1888, that doubtless involved a plug for the party’s presidential candidate of that year, Benjamin Harrison of Indiana, who was extremely popular in the Midwest for his stance on strong tariffs and other matters crucial to rural Americans and regional manufacturers.

Because of his early death at a mere thirty-three years-old, George Ingersoll never had time to be a present force in the lives of his two young sons, Charles and William (Grandpa Brown), and he was already gone a full six months by the time the youngest boy, John, was born. Instead, his impact on the family was devastating in its brevity. His legacy was his death: the premature withering of what might have been a new and blooming branch on the Ingersoll tree. For whatever book-learning George imparted to the many children under his public-school charge over the years would never trickle down to his own sons. Likewise, whatever direction he might have provided them in the way of alternate examples for their futures or the nurturing of aspirations never came to pass.

Shortly after George’s death, Mary (Rooksberry) Ingersoll left southeastern Illinois with her boys, moving them to the Peoria area and marrying quickly thereafter, quite probably because it was her only ticket out of destitution. As we’ve seen, this marriage did not last. Then, in 1903, she wedded an erstwhile bachelor farmer named William Bitner and relocated with the boys to nearby Elmwood.

In the course of all of this uprooting, Grandpa Brown ended up with a mere fourth-grade education and an early immersion into the workforce, where his lack of thorough schooling ensured that he would never advance beyond the pay grade or status of a common laborer.

As is now apparent, the early departure of a family outlier in the form of the father set a course for Grandpa’s life before Grandpa even had a say in what that course might entail. There was never a place, nor a chance, for aspirations. Instead, there was only work and impermanence, and the sense going forward that job security—or really any form of security—would always hang in the balance of economic swings, happenstance, and the whims of higher-ups. It’s no wonder that Grandpa clung to work the way others cleaved to their religions. Small wonder that he lived with a chip on his shoulder and fought so vigorously against people he thought might want to bring him down. No wonder he could become so wracked with worry over matters outside of his personal control.

And no wonder he took the dramatic step to change his surname and get out of Illinois as quickly as he could for what he must have hoped was a new chance at life in the west.

And as things turned out, Grandpa did find that chance in North Dakota, or perhaps it’s just as accurate to say that chance found him. The key to this chance, the manifesting force, was a young and lonely woman on a farm who was herself ripe for change. So ripe was she, in fact, that she not only chose to abandon her new husband and face all that that leaving would unleash in terms of stigma and uncertainty, but she also willingly cut ties to her own parents, brothers, and sisters, as well as any friends that she may have known her whole life up to that point.

She would never see any of these people again.

That was quite a gamble for someone who would later fret over her kids and grandkids shaking dice and staking pocket change on hands of poker at Thanksgiving. But this uncharacteristic “all in” attitude at the right juncture paid off in positive ways, and the union that she and Grandpa established early in the second decade of the twentieth century formed its own new and blooming branch. The legacy they passed forward was cohesion and continuity.

We cannot know today exactly what that young woman, the future Grandma Brown, sought to escape in 1910. Perhaps it was her unhappy marriage to an older man, maybe the pressure of family expectations, or something entirely different. Suffice it to say that whatever the reason, it was compelling. And I think it is also interesting to note that, while Grandma’s first husband, David Henderson, would eventually remarry in Montana, he would only live another four years afterward, dying in 1921 without issue. Grandma, on the other hand, married (or didn’t marry) Grandpa, and their union produced five children and made possible the lives of seven grandchildren and a host of descendants up the line.

Who knows what universal energies conspired to bring these two black sheep together and set them on this unlikely, prolific trajectory? You and I have those guiding forces to thank for our very existence. But the circumstances surrounding Grandma and Grandpa Brown’s union—namely, their abandonment of families of origin, the anger and heartbreak their leaving unleashed, the sense of longing and unresolved mystery their relationship passed forward—each emit their own vibrational echoes. And just as those echoes reverberate in the present, and manifest in our familial traits of worry, anxiety, codependency, and other self-destructive behaviors, they also remain in the distant and heretofore unknown past, where the offenses occurred.

For a truly generational healing to be complete, I believe it should extend not only into the future but back in time as well. It is with this in mind that I came up with a gesture that, while symbolic in appearance, I hoped would also facilitate some real reconciliation through the vibrational power of directed intention.

Last fall, I made a trip down to Crawford County, Illinois to do some research and to find out what I could, now that I finally knew the correct names of my paternal ancestors. On the way back north, I planned to spend a couple of days in Peoria and Elmwood, doing much the same. Before leaving La Crosse, I stopped at Grandpa’s grave at Oak Grove Cemetery, where I scooped up a few garden-trowel-sized bits of sod and bagged them up. My hope was to locate the two separate gravesites of Grandpa’s mother and father in Illinois and transplant the sod samples from Grandpa’s plot into theirs. And to complete this rite of sorts, I would extract the same from the Illinois graves for replanting back at Oak Grove. And if I happened upon other key ancestors, I might repeat the process just for good measure.

The research portion of my trip to Illinois was fruitful and went largely as I’d hoped it would. I finally accessed a copy of Grandpa Brown’s birth certificate that proved unquestionably his identity as William Elmer Ingersoll, born November 3, 1889 in Palestine, Illinois. And my search afforded some unexpected discoveries too. For one thing, up in Peoria, I located the death records of Grandpa’s mother and his brother, Charles, and, after reading about their respective demises, the sudden understanding of the extent to which madness and suicidality must have hounded them and their loved ones at the end hit me in my gut like a tossed cannonball. Talk about vibrational echoes.

Poring over microfilms in the Robinson Public Library over the space of two days, I was also able to access local newspaper references to the daily life of Grandpa’s father, George Washington Ingersoll, that helped me to flesh out the character of a man who, until just recently, I never knew existed. And while I suspect that I only found a smattering of available references (I simply didn’t have the time to cover the newspapers page-by-page over a span of decades), I was surprised by the way I came upon the ones that I did.

It was like a lucky streak with a Vegas one-armed-bandit. I’d scroll slowly, deliberately through the pages; then, when I’d glance at the clock on the wall and remember that time was in short supply, I would press the fast-forward control on the microfilm reader and send the reels spinning. So many times, when I did this, the machine would stop dead on a news brief (sometimes only a single sentence) featuring “G. W. Ingersoll.”

It was uncanny, almost as though my search was guided by unseen hands. In one newspaper reference, George Ingersoll had come to Robinson on business and randomly stopped in at the newspaper office for a visit. In another, from 1889, he expressed satisfaction over his mercurial little family’s newest living situation in Oblong township, where he was teaching at a one-room grade school with the colloquial name “Smoky Row.” At the beginning of 1891, the teaching job might have been wearing on him a bit, because he’d intimated to a reporter his intention to return to a study of law. And later that same year, he announced that he and his family were planning on moving back to Robinson.

Finally, and sadly, on March 29, 1893, the Robinson Constitution remarked that the little school in New Hebron where George Washington Ingersoll then taught had closed for the season on a Thursday rather than Friday, due to the sudden onset of the illness that would, in a short space of time, kill their beloved teacher.

***

One thing I could not do on that trip into Illinois was to locate the gravesites of my great-grandparents, George and Mary. I knew from his obituary that George Washington Ingersoll was interred somewhere at the Palestine city cemetery, but neither cemetery records nor a thorough canvassing of the grounds revealed the precise location of his plot. And available records for Mary did not list a specific cemetery interment up in Peoria county.

But I did find the gravestone for George’s father and namesake in the Palestine cemetery. George senior was a lifetime farmer, and, for a period of eleven years, concluding in 1873, he also served as minister at the Wirt Chapel Christian Church in Oblong township.

Grandpa Brown never knew his grandfather, since the man died in 1877, some twelve years before Grandpa was born. Still, ever since discovering this new information about our family, I’ve been struck by the fact that Grandpa, who never seemed to give church any credence, descended directly from a preacher of the Gospel. Perhaps that was another branch that withered with the death of a principal influence, altering our family trajectory from one of fervent faith to one of relative non-commitment. I don’t know if this is how it played out or why, and I don’t feel the need to explore here whether it’s a good or bad thing, but the fact remains that, with but a few exceptions among the cousins and cousins once removed, there has not been a strong tendency among Grandpa’s descendants to embrace organized religion.

The day was getting on in Palestine, and since there was no chance of finding the gravesite of Grandpa’s father at the city cemetery, I decided to spend my limited time in a more promising location. Still, I thought the old preacher, my great-great-grandfather Ingersoll, deserved recognition, if not a dose of energetic healing. So, I walked back to my car, grabbed the garden trowel and one of the sod pieces from Oak Grove. I dug out a sample from the lawn around his grave and dropped it into a separate gallon zip-lock baggie. Reaching into the other bag, I fetched an Oak Grove sod piece and patted it down into the little hole and paid my respects to the man, thanking him for his role in making my life possible. Then I put the trowel and the baggies in the back of my Buick Encore and drove out of Palestine, toward New Hebron.

***

On the evening of March 22, 1893, Grandpa’s father stopped for the night at the residence of an older widow, Hetty Cawood, near the tiny village of New Hebron—the place where he’d taught school since the previous year. I likely will ever know for sure the connection between Hetty Cawood and Ingersoll. Perhaps the widow took in boarders or was a family friend. Or maybe she was somehow connected with the school. Whatever the case, around nine o’clock that evening, George fell ill; more specifically, in the words of his obituary in the Robinson Constitution, he “was taken with a chill and a severe pain in his side.” Hetty Cawood summoned a local physician, Linus Gilbert, who determined that George had contracted bilious pneumonia—a serious infection of the lungs that occurs when a patient aspirates bile from vomiting. The next day, a Thursday, the school at New Hebron had to close a day early for the season due to their teacher’s absence. According to the Constitution, this inconvenient onset of illness disappointed the young teacher greatly, as Friday was to have been his last day at this post. He’d accepted an offer to teach in nearby Flat Rock for the next term.

But that was not to be. George’s condition worsened, and he lingered in this fevered state at Mrs. Cawood’s residence for a grueling nine days, finally dying around 3 a.m. on the first day of April.

New Hebron was the last place where George Washington Ingersoll drew breath. It is also the place where his life energy left his body on that April morning. If I could not find the precise location of his physical remains in Palestine, I figured the next best thing would be to pay a visit to the site of his death.

Just outside of New Hebron, on a lonely road in a wooded area, I pulled over to the shoulder. Without knowing specifically where the widow Hetty Cawood had lived in the area, I figured this to be as good a place as any. A pickup truck with two young men in it had been behind me along the way, and they zoomed past and headed up the road as I got out and opened my back hatch to retrieve my trowel and an Oak Grove sod sample.

I didn’t want to dig in “new” earth—that is, stuff that was likely deposited for the roadbed. So, I walked into the brush, and I was beginning to descend a little embankment toward what I think may have been a creek when I heard a vehicle slowing down. It was the boys in the pickup that had passed me moments before. I slipped my trowel and sod into my jacket pockets and stepped out to the roadside to meet them.

“You need help or something?” the driver asked.

“No, thanks,” I replied. “I’m just….” I hesitated. Did I really want to launch into an explanation that I was out here to affect some otherworldly spiritual healing with a long dead ancestor?

“I’m just out enjoying the weather down here,” I said finally. “Thought I’d have a little walk in the woods. Back home it’s near freezing and there’s snow coming.”

“Whoa!” the passenger said, apparently impressed by the difference in climate I described. In truth, I had no idea what the temperature was back home.

The driver didn’t seem quite as affected. “So, you’re good then?”

“Yeah, thanks. I’m good.”

The kid nodded slightly and shifted back into drive. The truck did a U-turn and rumbled back up the road. I walked back into the brush and quickly did my sod extraction and transfer.

***

Two days later, I was up in Peoria County, walking through graveyards in Elmwood and surrounding townships, searching for Grandpa’s mother, Mary Rooksberry Ingersoll, under her third married name of Bitner. Once again, I turned up nothing; so, once again, I opted for the next best thing. That night, back in my room at the Mark Twain Hotel in downtown Peoria, I got on Ancestry.com and pulled up the 1910 Federal Census page showing Mary and William Bitner living in the rural lands near Elmwood. I took note of the family names of people who lived in proximity to them. Because census enumerators of the day would travel deliberately from residence to residence to collect information, even in rural areas, it is possible to narrow down the approximate places where people lived. Next, using Google, I located an 1873 Elmwood township plat map that showed the boundary lines of individual properties, as well as the last names of families who owned them. The map may have been compiled a little early for my purposes, but I also assumed that many of these families had farmed the same tracts of land for decades. Who knows, I figured, it might turn up something.

Sure enough, it did. The two farm families that followed Mary and William Bitner in the census enumeration, Gibbs and Miles, showed up in that old map in the same order along a straight stretch of road, now known as Tiber Creek Road. This tells me that the census enumerator had traveled from west to east that day in 1910, gathering names and information, and that Mary and her third husband resided close by, somewhere to the west of the Gibbs property. Pulling up a recent Google map image of that stretch of road, I was able to pinpoint with relative certainty the area where the Bitner’s small farm must have been.

That’s where I would perform my ritual transfer of sod. After all, the land around Tiber Creek Road was ground that Grandpa Brown had trod upon from the time that he was thirteen until about eighteen, along with his brothers and a handful of cousins on the Rooksberry side. The wide-open spaces must have been quite a change from that time between 1895 and 1902, when he’d lived in bustling Peoria. I can imagine them taking hikes, running through the fields, splashing in Tiber Creek, and, after it opened in 1905, catching the occasional wagon or carriage ride back into Peoria to visit Al Fresco amusement park. A photograph I’ve recently discovered of Grandpa Brown, taken at a studio in Elmwood, shows the sullen-looking, pubescent kid in a dark jacket, shirt, and necktie. There’s a decorative brooch on the lapel enclosing a picture of Grandpa’s mother. And in the middle of his tie, Grandpa sports a pin that reads “Meet Me at Al Fresco.”

I drove back to Elmwood the next day and parked along the side of Tiber Creek Road. I wanted to walk the straight, mile-long stretch between my parking spot and the T-intersection formed by North Bell School Road, near where Tiber Creek Road crosses the stream that it was named after. This is the land where Grandpa spent those five formative years. It is also the area from which he eventually escaped with the aspiration to become a cowboy in the great, unknowable future that North Dakota represented for him.

As is usually the case when I drive, I stream Spotify from my phone, beaming it to my car system through a Bluetooth connection. That day I was streaming one of my favorite playlists—a collection of popular music from the 1930s and early-forties. I shut off my engine and stepped out onto the road to begin my walk. When I did, the Bluetooth connection broke, and the sound source transferred from the car speakers back to my phone. A new song was starting randomly as I took my first steps, a ballad with a brief orchestral introduction. I smiled when I heard the rich baritone of Bing Crosby singing the opening line:

“I’ll be seeing you in all the old familiar places….”

Grandpa was here. He was welcoming me.

Somewhere along this stretch, they had lived. I walked a half-mile up the road, then out into a field. The topsoil was thick with roots. With some effort, I pushed the trowel into the earth and pulled up a sample. I filled the new hole with an Oak Grove sod sample and thought of Mary.

As a mother, Mary Ingersoll did the best she could with what life had given her. It couldn’t have been easy. According to her 1923 obituary, she had been orphaned early on. And before Charles, Grandpa, and John were born, she’d already lost two children during the first half of the 1880s, neither of whom made it beyond two years of age. Then, as we’ve seen, her husband George Washington Ingersoll passed suddenly in 1893, and Mary had to face the terrifying prospect of raising two young boys and a yet-unborn infant.

What followed was a frantic scramble to right the balance: that brief and failed marriage to John V. Schmidt. After that, there was a period of several years of living singly with the three boys in Peoria, just blocks from a noisome stockyard, earning what she could by taking in and washing people’s dirty laundry. Finally, in 1903, she married a third time, to William Bitner, a union that precipitated another uprooting: in this case, from a crowded urban existence to the comparatively staid, though no less demanding, life as a wife and a mother on a small farm of limited financial promise.

Once again (and, not surprisingly, much like Grandpa’s experience later), hers was an existence whose quality hung on the whim of uncontrollable circumstances—in her case, here in Elmwood, on the fluctuations of climate and the market.

Surely, she loved her boys. And there’s at least some evidence that they loved her back. There is, for example, that image of Grandpa wearing the brooch with her picture. I can’t think of too many teenage boys today who would do such a thing, no matter how strong their regard. And the shot of that brief, final reunion of the brothers after Mary’s death is also telling. Aside from the simmering tension they betray in proximity to one another, all three grown men appear to be positively lost in grief and regret.

But most poignantly, there is a photograph from around 1920 of Mary with her youngest child, John, and an unidentified young woman, in which the three of them are standing together in front of an old farmhouse, so close that their shoulders touch. John is wearing a print apron, so they might be taking a break from kitchen work. None of the three appear too thrilled to be in the picture. The young woman looks entirely unamused. She scowls at the camera, holding her arms behind her back as though she’s a soldier standing guard. Both Mary and John at least show a slight, one-sided upturn of the lips that could pass for a cautious smile. I’ve seen the same expression preserved in images of Grandpa and the older brother, Charles, but it certainly isn’t characteristic of John, whose photos typically show him grinning widely or acting playful in some way. Perhaps his recent Army experience in Europe had tempered his boyish joie de vivre, or maybe he’s concerned over his mother’s declining state of health.

Mary stands in the middle of the shot, between John and the unidentified woman, and it looks as though her right arm might be resting against the woman’s back. But her left arm is visible to the camera, hanging low to her side with her hand turned slightly inward. And her little finger is enfolded lightly but lovingly in John’s hand. It is a touching, telling gesture.

***

But even with these bits and pieces that demonstrate a shared regard, I’m still left to wonder whether Mary might have played some part in Grandpa’s decision to leave Illinois. While I’m sure that family dynamics had to have played a role, it is hard to draw any solid conclusions that single her out. Besides, the evidence is mixed.

On the one hand, you and I have what we had to go on before all of this happened, which was Grandpa’s silence. This alone speaks volumes, especially given what we now know, and it can only suggest that he had reasons beyond mere secretiveness to do so. What about his past troubled him enough to deny his own children the story of its family origins? It wasn’t like those cases of a kidnap victim or a war survivor who refuse to discuss the specific incidents they suffered through. Grandpa withheld the entire first twenty-eight years of his life as if they’d never happened.

As you claimed, it truly must have seemed that the world began when you all were born.

Of course, Grandma didn’t reveal her past either, which opens the possibility that the circumstances of their union precipitated the cover-up. Granted, even though it isn’t such a big deal nowadays, a wife running off with another man was a big deal then, one that carried real consequences, social and otherwise. But even if their tryst was the event that precipitated their lifelong concealment, why did Grandpa choose to minimize and eventually sever ties with his mother and brothers in Illinois, who really had nothing at all to do with the part of his story that centered around Grandma? And most importantly, why did Grandpa later take the dramatic step of inventing new names for his parents on his Social Security number application? He did this in 1936, when he was nearly fifty years old!

What did Grandpa have to hide that late in the game? Who was he hiding from? And who at that point would really have cared one way or another?

On the other hand, there is enough indication that, despite Grandpa’s unwillingness to share his past with you and your siblings, he had nevertheless kept a connection, if only a tenuous one, with his own mother and brothers at least into the early 1920s. Included in mother Mary Ingersoll’s photographic keepsakes, for example, is a handsome portrait of Grandpa Brown taken around 1910 at a studio in Wahpeton, North Dakota. I think he resembles one of Genevieve’s grandsons in it. At this time, he was either on the verge of meeting his future life-mate or had recently done so. It is likely he mailed the portrait to his mother back in Elmwood (and I think it’s not insignificant that she kept it all those years, and that John Ingersoll retained it after she died).

Yet another photo shows Grandpa and another man, possibly a Rooksberry cousin, standing on a wooden footbridge that crosses Tiber Creek. Taken near where he once lived outside of Elmwood, I estimate this shot to be from around 1918, based on the clothing and the fact that, compared with the earlier photos of him, Grandpa appears here to be in his late twenties. Might he and Grandma have journeyed to Elmwood to show off their first-born daughter, Genevieve? I think that is a distinct possibility.

And speaking of Genevieve, there was that portrait of her as a baby that, as I discovered to my everlasting astonishment, Mary also possessed.

So, it is now clear that Grandpa’s connection with his mother and brothers remained for a little more than a decade after his departure for the Dakotas. Then, after Mary died in 1923, he traveled to Peoria county with Grandma and little Genevieve one more time. Quite probably, he left them in Peoria while he attended to his private family matters near Elmwood. He saw his brothers there, as is evidenced in the photo of them standing together on some rural property, possibly Charles’ farm.

Genevieve, as we’ve seen, recalled that train trip down and back, and her salient memory is of Grandpa appearing mournful, tearful, on the return to La Crosse. Grandma tried to quiet Gen’s concerns with shadowy explanations: He’d gone down to see someone, she said. Something didn’t work out. So Genevieve learned early on to suspect that there was a familial past back there—a sort of origin story with characters, and trials, and lessons—but she also learned that she could never know anything about it, and certainly could not participate in it.

Gen, with her childish queries over her father crying on a train, might have opened the door for all of us back then. But Grandma closed it quickly, and it remained closed. None of you other kids ever got as close as Genevieve did on that day to breaking through.

And that’s how it stood. For nearly a century that nothingness was all we had.

That is, until now. And maybe my having done the difficult and often frustrating work of drawing together the disparate strands of our family story is one of my lasting legacies, a blooming branch of my own making. And perhaps by laying this story down here, we might not only go forward armed with a better understanding of what has worked out favorably and what has held us back as descendants, but also, having finally reawakened the memory of ancestors long concealed, we might affect some energetic repair in the past, quiet the echoes that have haunted them, and us.

It feels strange to say this, Dad, but a part of me wishes that you could have lived long enough to hear these stories. But for all I know, you might have been the unseen hand guiding me all along.

***

It is the middle of May 2020, two days before my fifty-seventh birthday, and I’m back at Oak Grove Cemetery. This time, though, I’m walking. The whisper of spring I had sensed while sitting in my car in March has now become a full-voiced proclamation. The temperature today is in the seventies. Most of us are still distancing ourselves socially from each other in hopes of lessening the intensity of this worldwide COVID-19 pandemic, and I’ve found during this time that the cemetery is one place where a person can walk without having to pass too closely to others.

The lawn surrounding the graves of Grandpa, Grandma, and Raymond is now in full growth. Kneeling on the grass in front of Grandpa’s headstone, I can feel the slight indentations left when I filled the original holes that I had dug with sod samples from central- and southeastern-Illinois. Those tiny circular spots are producing growth of their own now too: a few shoots of grass, some clover and gray speedwell. Just over by Raymond’s stone, there’s a decorative cement jardiniere bearing the dry and dead remains of last year’s blue begonia. As soon as I’m able to enter a store again, I’ll need to replace it with a fresh plant.

I look forward to a return to normality, but to be honest, the quarantine period has gone far better than I’d expected. I thought I’d be climbing the walls being basically cooped up for months. I’d wondered whether my anxious tendencies would overwhelm me in close quarters.

This hasn’t happened, however. Not that it hasn’t been annoying or problematic. But I really haven’t felt that long-familiar weight of dread in my belly so much. Of course, I still find myself tethering to outcomes, still catch myself being codependent with crucial people in my life. But the key is I’m catching the behavior and catching it sooner. Not only that, but I’m also recognizing it for what it is and questioning whether it is so important or necessary for me to feel that way anymore. More and more lately, the answer is “no,” and I act on that answer. This is progress of a sort. And like we say in the program, it’s all about progress rather than perfection.

I cross East Avenue and enter the old section of the cemetery, where the larger, more ornate monuments stand. Here is where one finds the towering obelisks, pensive angels on pedestals, family crypts, the large tree-trunk gravestones with simulated bark that were popular in the 1890s. This section is also where most of the prominent figures in the city’s history are buried—the state senators and Civil War officers, the industrial moguls, and others of the well-placed strata.

Walking through this section of Oak Grove, it is easy to be so taken in by the necropolitan splendor that I lose sight of the majority of the stones here: the modest memorials to everyday folks (though even these often appear ornate by today’s standards). A look at the names inscribed in stone at Oak Grove provides a snapshot of the northern-European makeup of the city during the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries: German surnames like Bedessem, Putsch, and Schumacher. The Scandinavians—Dahl, Ruud, and Everson. Bohemian names like Verhota.

Lately, with so much of the news and general discussion focusing on the current pandemic, I’ve begun to note stones dated 1918, the year of the so-called “Spanish Flu.” According to sources I’ve read, La Crosse fared better than many other communities. Nevertheless, it took a heavy toll, noticeably among the young. Near the East Avenue entrance of the old section there is a row of nine flat stone markers—each of them from 1918, all of them marking the burial place of babies or small children. Curiously, the last names are all different, and none of them have accompanying relatives buried nearby. It was as if these children had perished in close succession to one another and were buried in that order. Walking through and noticing other stones inscribed with an end date of 1918, I see many young adults.

Local newspaper obituaries fill in the details for some of them. Among the fallen were young brides and grooms, nursing students who’d been working their first shifts in the quarantine tents, servicemen from World War I. One of these last individuals, Kurth Fuhlbruegge, a private in the U.S. Army 24th Medical Unit, died of influenza at sea aboard the transport ship, Martha Washington. One can only wonder if he was helping fellow shipmates through their own bouts with the virus before he fell prey to it himself. Private Fuhlbruegge was twenty-nine years old when he passed. He’d been born the same year as Grandpa Brown.

I think of these young people whose lives were cut short, especially the babies, and it strikes me that both Genevieve and Raymond came into the world during this very time of national health peril, being born in 1917 and 1919, respectively. Somehow, they survived the Spanish Flu. Incidentally, so did their parents, Grandma and Grandpa Brown, who went on to have three more kids in the 1920s—Elaine, Kenneth, and you. And together, all of you Brown children except Raymond eventually had babies of your own. And we kids have had ours. And on, and on.

It boggles my mind to think of this spreading out into the future, just as it does to consider what has come down the lines from the very beginning. Each member of a particular generation can glance both forward and backward in time and realize a sort of Indra’s net of probability exists on either side. You are the result of a long line of learned survival skills, as am I. My kids enjoy the same advantage; and if they have children themselves, the net will spread accordingly. Somehow, every one of your direct ancestors and mine have survived wars and hostile situations, avoided accidents, have made it through the Black Plague and all similar scourges throughout time. And one can extrapolate this lucky streak as going all the way back to a handful of unnamed proto humans, each of whom had the fortune (or was it fate?) to run faster than the next fellow to escape some bounding cave bear or saber-toothed cat. Somehow, they all cheated death long enough to have children of their own. And we came about because of it. Life is utterly amazing when we consider those stakes and the odds overcome.

But, as we’ve seen, we don’t simply pass down our physical resemblances, names, and dates. We also pass down tendencies, challenges, attributes, predispositions to this or that. Stories and haunting memories that take on a life of their own and reverberate far into the future. We pass down behaviors, both the helpful kind and the not so helpful. We make mistakes along the way that others can learn about through our example and thus seek to avoid. And we sometimes discover novel ways around or through difficulties so that those who come after us need not reinvent the wheel.

Sobriety is perhaps another fruitful twig on my blooming branch, and I say this with full recognition that I’ve only played a limited part in bringing it about. Some have suggested that my quitting alcohol and drugs in the late 1980s was an impressive feat of willpower. I quickly and firmly disagree. The truth is I have no willpower when it comes to my addictions. Life has proven this to me over and over. The power I draw from, the power that took away my desire to use mood altering chemicals, is a force beyond my understanding or ability to define. Call it God, or the universal mind, or Oden, or one of those lesser gods of myth that come down to tinker with the lives of humans. Or don’t call it anything at all. Personally, I’m not too interested in pinning a name tag on whatever it is that saved me. I’m just thankful it happened.

But what I have done is the necessary human footwork. I attend the meetings. I try to take care of my physical and mental states. I endeavor to learn from my mistakes. I seek help when it’s needed.

And I try to keep in mind that others who might need an example are watching my every move. You yourself were watching, I know. Even though you made the decision somewhere along the way not to pursue a life free of alcohol, you always expressed happiness over the fact that I had done so. From the time I sobered up until the last year of your life, you always remembered my anniversary of January third. Not only that, but you remembered how many years each anniversary represented. I can never express adequately how much that recognition meant to me.

I admit this part about others watching is the most humbling and often the most challenging aspect of my conscious behavior, because I know that I’ve not always been up to the task during my three decades on the wagon. I have often let my depressions and anxiety episodes spin dangerously out of control before doing something about them, even to the point of considering suicide. I have manipulated people to meet my codependent needs. I’ve saved my children unnecessarily at times to avoid conflict and to satisfy my selfish, often desperate craving for love; and in that way I’ve denied them the growth opportunities that problems present.

But again, it’s progress not perfection. I am progressing today, a day at a time; and it all leads back to that morning in January 1987 when I put the plug in the jug and began this journey of recovery and self-improvement. I can only hope it’s making a difference going forward, but time will tell. Early evidence suggests we might be on a positive trajectory.

Your grandkids are now carrying it forward, living their lives as adults—free to make mistakes and grow, and to realize triumphs as well, hopefully with minimal interference from yours truly.

As I had indicated in passing as I wrote this, Dylan suffered through a long and dangerous rough patch that lasted into his early twenties, part of which you witnessed. His world at that time was one of drink and hard drugs, violence, and scary brushes with the law. But he had a major health scare with a bout of pancreatitis at about twenty-five, and he sobered up then and there while still in the hospital. He went back to school after that, and, like me, he discovered his own work ethic and a life path of his choosing. Most recently, he bought the old house on Hoeschler Drive and lives there today—the third generation of Browns to do so.

I’m happy to report that he’s been clean for nearly a decade now and is a walking success story. He’s always been a caring, loyal, organically intelligent person. But now he is in the process of becoming a wise one too. His way of making sense of the world both astounds and entertains me, and I look forward to our many talks of late over the phone or via Facebook messenger on politics, history, and the favorite movies we share in common.

I could not be prouder of him, and I know you would be thrilled to see the man that he’s become.

And Sophie? That beautiful young lady just turned nineteen in April and is living on her own now and finding out what all that means. Her adult adventure is only beginning. One thing is certain though: Sophie is ten times the musician I’ll ever be—a fact that’s been clear since she was around seven or so. She kept up with the cello-playing journey she embarked upon as a three-and-a-half-year-old, and she has received countless accolades along the way. Much of her skill in the music realm, I believe, came down from Mom’s side of the family: a raucous ancestral collection of vaudevillians, colorful rogues, and circus band players that probably deserve their own book-length treatment.

And speaking of musicianship, remember how you always used to tamp down my runaway rock-star aspirations by assuring me I’d “never make it to Carnegie Hall”?

Well, it turns out you were right. I never played at that storied venue, and at this point I never will.

But guess what?

She did.

This is all so interesting. I remember way back when you and your Mom discussed the possibilities of the Brown secrets. They would both be very proud of you and your kids. Your Mom would be in awe of Sophie’s musical talent ! They also would love your current family and how happy you have become !!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Again this chapter brings back so many memories for me. Would love to go visit my husband’s grandparents graves in Oak Grove but with La Crosse Street torn up I don’t know that we could find our way. Because of our age 80 and 81 this will probably be our last trip here to the La Crosse area. So all that will remain is memories and pictures of the area and the good times we had growing up here. We grew up in the best of times.

LikeLike