Ringside Seat to a Downfall

I can muse over the wherefores from now till the end of time and not come up with anything definitive, but I think I’m safe in claiming that one reason I’ve never carried out my suicidality to a fatal conclusion is because I am, by design, a survivor.

Codependent people have a keen, learned capacity for getting over. As a card-carrying member of that demographic, I have spent six decades micromanaging situations to minimize conflict, hurt, or upset. I cover up or conceal other people’s bad or stupid behaviors to save them from consequences, especially if I perceive that those consequences might somehow ricochet back in ways that harm me. I’ve done this with friends. I did it with you and Mom in the early years, when kids in the neighborhood razzed me about what they termed your “problem drinking.”

I’ve even done it with my own children when I rescued or shielded them from the natural consequences of their missteps. You once revealed that Grandma Brown had a similar, recognizably codependent strategy. When you or one of your siblings got into trouble, she would often address the matter herself and bypass Grandpa, who, during the day, was always away at work. According to you, she was afraid of triggering him into a state of worry or perhaps some other, more volatile emotion.

I often avoid speaking my mind when people who matter to me do me wrong. I’ve learned the hard way that speaking truth to power can bring on a shitstorm of trouble. But I never forget the wrong either, and I will surely exact revenge on that person at some point with a calculated and perfectly deployed act of passive-aggression (which I will immediately regret and attempt to win back their favor and esteem by overdoing it with enforced kindness).

I might come across as pacific and easy-going, possessing some innate faculty for negotiating between warring parties. That’s because I’m good at it. I’ve made it my life’s work, having learned the ropes early with you and Mom. It’s no coincidence I once considered a career in public relations, and even worked in that capacity for a time.

Still, this aspect of my personality is not completely disingenuous. I truly do like people and wish them well more often than not. But in the end, it’s quite possible I’m also angling for a payoff in the form of good vibes thrown my way, or perhaps I’m working toward some other future advantage if that advantage ultimately spares me from hurt or upset.

Of course, when I feel as though I’m playing with a weak hand, I can become a dictatorial control freak, battening down every facet of my life to guard against variables, or badgering loved ones in a quixotic attempt to bring them to heel and thus restore order to my world.

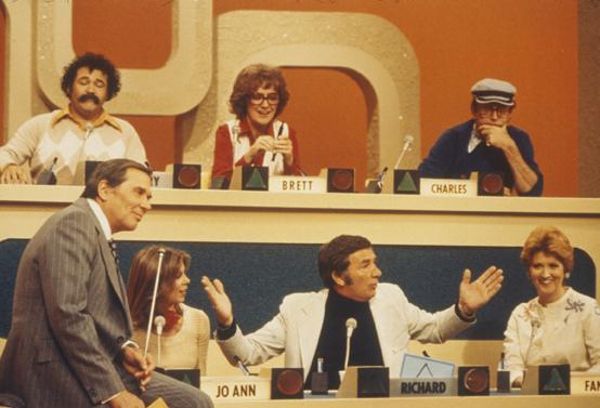

I am hyper-sensitive to people’s vibrations. If someone close to me is having a bad day, I will home in on that frequency and make it my own. If they are sad, I will assume the task of making them feel better, because a happy person in my midst is far easier to bear. If they are angry, then of course their ill-temper must have something to do with me, and I will take on a sense of guilt, even though I haven’t a clue as to why. I even pick up on the emotions of strangers. I recall as a kid in the early 1970s watching “Match Game” on TV, and I’d have to turn off the set if contestants blurted out dumb answers that resulted in their embarrassment.

Perhaps it’s no surprise that I often live in self-deception regarding my own motives. But of course, in my most candid moments of reflection (as I write this passage, for instance) I also glimpse the truth that there is a profound difference between being empathic or giving-of-self and acting out as a codependent person. For in the throes of active codependency, I really don’t seek peace, control, beneficence, or calm for their own sakes. Instead, mine is often a self-serving coping behavior, the motives for which essentially boil down to the attainment of personal safety: safety from the threat of physical harm, from emotional abuse; safety from abandonment or want; safety from responsibility over “setting someone off”; safety from having to choose between two loved ones engaged in bitter conflict; safety from conflict between myself and others; safety in the form of refuge from the real world of cause and effect; and, of course, safety from the universe of outcomes that I cannot control.

This last bit is critical to an understanding of my codependency or, for that matter, my addictive behavior too. The very fact that I have striven over and over in this lifetime to manipulate potential outcomes to shine in my favor is both my folly and my delusion. Victories might be won along the way, but their significance is mostly realized in the short term. In the long run, it is like trying to displace an ocean of water by wading into the tide. It cannot be accomplished in any permanent or efficacious manner. Variables abound.

Nevertheless, if I leave my conduct unchecked, un-inventoried, I will set out to do it every day, in every way. If only this specific thing can be addressed, then all will be well going forward. If I can just prevent this or ensure that….

***

Last night I dreamed that I had to testify at a court appearance in some action against you. I don’t recall all the details (I seldom do in dreams), but I do know that I had initiated the action. You and Mom showed up as the trial was commencing. Mom was drunk, muttering to herself and glaring at everyone in the courtroom. As you entered the space, you voiced some threat of physical harm to the judge and were summarily arrested by the bailiff. Mom’s sister, Betty, along with a few other of our relatives, were all seated members of some grand jury-type of deliberative body to which I delivered my case against you.

Later in the dream, I was back home to pack up my things and leave. You showed up unexpectedly at the house, saying nothing but wearing a tired expression on your face and a slight, almost embarrassed smile. But it was no olive-branch moment. I had stuck to my guns during the court procedure, and I had won the case. Consequently, you and I were finished. I was out of the inheritance, left to fend for myself in life. Despite this seismic shakeup of circumstance—or, as the dream seemed to suggest, because of it—I gathered up my few belongings and walked contentedly out to spend my first night sleeping on a huge boulder beneath a highway overpass.

Of course, things didn’t go that way in our real life. Outside of that one fight over Mom’s nursing home care in the early 2000s, I never did stand up to you in any fundamental, relationship-threatening way, as I probably should have on many, many occasions. I never called you out sufficiently or erected sturdy and permanent boundaries between us during our life together. Instead, I often took the road of least resistance, perhaps shouting out a few objections over time but never enough to upset you beyond repair and disrupt the tenuous and, as it became over the years, transactional relationship we shared.

Even at the end of our brief separation after our blowup and the letter I’d sent (when you and I patched things up with a few quick words while standing before the casket at Mom’s visitation) I settled into a private rationalization: Going forward, I would bide my time, tolerate our situation as best I could, keep my mouth shut and, to put in frankly, take the mercenary path and await the payoff of my inheritance and the opportunities it would afford me.

More and more, I began to see that there would be distinct advantages to living in a world without you, the primary one being that I might finally crawl out from the pall of your long shadow. Once there, I could at last forge the existence I’d wanted all along: to live a life of unbridled creativity and intellectual expression. A personal version of “my own man” that you never would have understood.

***

Ernest Hemingway, in summing up the title character of his story, “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber,” could as well have been describing my coping strategy when he wrote that Macomber “had always had a great tolerance which seemed the nicest thing about him if it were not the most sinister.”

Like me, Macomber had also lived a meek existence for much of his thirty-five years. Tolerating his way through a life governed by fear; living self-consciously in the shadow of overt males such as Robert Wilson, the robust safari guide; cuckolded and pushed around by his strong-willed and calculating wife, Margaret, Francis Macomber came into his own as a man late in life (the final day of his life, in fact) during a thrilling hunt for water buffalo on the African savannah. He described the near-instantaneous transformation as being like a bursting dam. “You know,” Macomber remarks after a perilous pursuit of three massive bulls, “I don’t think I’d ever be afraid of anything again.”

Wilson recognizes this change in Macomber, and it moves him deeply. The hunter “had seen men come of age before,” knowing too that transformations like these were not simply “a matter of their twenty-first birthday.”

Margaret Macomber sees it as well, but her reaction is one of trepidation and seething resentment. She realizes that her days of controlling Macomber are at an end.

I don’t know whether it happens quite like Hemingway describes it: a man irrevocably transforms from tolerant patsy to “ruddy fire eater” through the crucible of a single event? At least, such a thing has not yet happened to me. In fact, I can say that I have not been truly, fundamentally self-possessed since that night in 1965, when I strolled off into the dark on my own to chase fireflies.

Of course, being a toddler, I didn’t know any better. And really, that is the point. Somehow, between then and now I unlearned the capacity for absolute confidence with which I was born. My sense of self transformed from being a natural thing which I took for granted—a gift of the universe—into something qualified, subjective, and dependent on the validation of others. Not that everyone doesn’t go through something similar in their own development. They do. It’s called growing up and recognizing that others exist, and that as social animals we must learn the ways of our peers and learn to coexist with them. One key to success is the setting of limits, and the learning of ways to stand up for oneself over things that matter.

Unfortunately, I missed out on that part of the learning process early on. And whether people truly experience Macomber-like moments of transformation, I only know that I could have used one along the way.

What would something like that have looked like for me? For starters, it probably wouldn’t have happened on a hunting trip. Certainly, it would have been best to have happened sooner than later. Something definitive, probably dramatic and wrenching, that would have set the tone unmistakably for all future interactions with people. But again, to be most effective it would have to have started early on, in childhood.

And the first instance would have to have been at the source of my codependency: namely, my relationship with you. Crucially, it would need to have involved me saying “no” to you in no uncertain terms.

No. No. No. No. No.

Easier said than done. The initial response to my setting a tough and unmistakable boundary would have been physical and terrifying. Like the time when I was in first grade, and you had scolded me about something. I don’t remember what, but I remember we were in the kitchen. I was sitting on the floor, against the wall. Mom was there too. You said your piece to me, then turned your back to walk to the refrigerator.

I saw my chance to defy and I shook my fist at you. Mom saw me and told you what I’d done.

The thud of your footfalls is what I recall next. I can still feel them today as I bring this up—your steps reverberating in the floorboards of my memory. Or maybe it’s my heartbeat. I can’t escape you, as my back is literally against the wall. You grab me with both hands, flip me over on my belly, and spank the living bejesus out of me for what seems like forever.

Two lessons I learned that evening: Don’t trust Mom for safety, or with secrets. And do not ever defy you.

But I can’t really blame this singular incident on my failure to establish and enforce healthy boundaries between us. All that did was set a precedent for what I might expect. Later, there would be many more spanks and slaps, pushings against walls, challenges to fight you, threats on your part to commit suicide or simply to go away. My conditioning happened over time. It was cumulative.

You would think I’d have gotten used to it along the way, or that I might’ve become desensitized. Perhaps one day, maybe in my late teens or early twenties, I might’ve even taken the opportunity to grab you by the shirt and push you against the wall for a change. Or I might’ve smacked you across the face or even put my hands around your throat. I remember a day at Sierra Tucson, hearing a man describe how, when he turned eighteen, he beat his overbearing father to the floor of his own kitchen till the old man cried for mercy. All I could do was listen to him, enjoying every minute of it, secretly wishing I too could have relayed a story like that.

Or maybe, just maybe, I might have done the healthy and mature thing and consciously set out to develop the ability to say “no,” and practiced at it every day by saying no, no, no, no, no to you and to other people until it became second nature. That alone probably would have changed everything. And I do mean everything.

That solitary act might have even healed a long, learned strain of dysfunction and turned the course for generations to come.

But unfortunately, none of those things happened. And along the way, I developed a pattern of tolerance and capitulation that, I believed, would serve to steer me clear of the fallout that comes from saying “no,” but whose real and lasting stamp has been to infect, and sometimes doom, just about every relationship I deem crucial. And this includes my own relationship with myself.

Even still, in my own peculiar, dysfunctional manner, I do find ways to get over. In the end, I survive. The means might not be healthy or productive. They might be outright sinister in their application. They will likely not involve direct action, but instead might be accomplished by way of a tactical end-run or some act of passive aggression or semi-intentional sabotage.

The final scene, however, will find me standing: a bit shaky perhaps, possibly diminished in my self-assessment, maybe wearing a simple band-aid over a massive, weeping wound.

But alive.

***

As your state of ill-health continued and worsened over time, and especially after Mom died, so too did my attitude about it. I’d long since given up hope that you’d sober up, and now I’d begun to take the opposite tack: If your lot was to die from the effects of your alcoholism—even if that was only a contributing factor—then so be it, and the sooner the better. Go for it. Keep on drinking.

It came to a point where I could identify with Al Pacino’s character, Michael Corleone, in one of the all-time great movies, The Godfather, Part II. In a pivotal scene toward the end, Michael Corleone is discussing with his cronies what to do about an older, rival mob figure, Hyman Roth, who has long stood in the way of Corleone’s desire to consolidate power. Michael wants to bump off Roth at the next opportunity. His adopted brother and consigliere, Tom Hagen, suggests waiting it out, playing it safe, adding that Roth’s health situation is terminal anyway, that he probably has another six months to live, if that.

Michael cuts Tom off abruptly, quips that Roth has been “dying of the same heart attack for twenty years.” And he orders the hit.

I had been anticipating your own departure from the time I was about ten, so that made it more than thirty years for me. And at some point, I slipped across the borderline separating “please don’t let it happen” from “why is this taking so long?”

In the last year of your life, I became obsessed afresh with the idea, though in a new and twisted way, and that obsession came to take over much of my time. I began to creep around your house at night to keep an eye on you, not to save you, but rather to find you. And I routinely drove the circuit of your hangouts during the afternoons and early evenings, just to make sure you were still in the habit of frequenting them. The hope for sudden cures or redemptions had worn out, and all I wanted now was the status quo. There was a Subway sandwich place directly across the street from one of those dives. It had a sunroom in the front that allowed me to sit and watch you come and go. That restaurant became a frequent haunt, a ringside seat to your downfall.

***

Rereading these passages today, I’m struck by how fucked-up evil this buzzard-like, voyeuristic obsession must seem. You were my dad, after all. Despite all the monstrous, negative things that had gone on with us, you were still my dad. Where had my sense of decency gone?

But the bottom-line truth is that your continuing survival—your dogged, annoying capacity to wake up each new morning, year after year—came to stand in the way of the hopes I had for myself, the dream of my life as an adult, as my own man. I’m not proud of my conduct then, but I did it. And not only that, but I did it enthusiastically.

I wish it could have gone another way, Dad, but it didn’t. In the final, bitter estimation, the sum of our life together had become a singular conclusion, one which has at turns soothed and haunted me over the years:

Your living postponed my becoming, and I wanted you gone.

You write with supreme courage and articulation. Bravo. I have come to realize that we are polar opposites in many ways. I am aggressive/aggressive and dependent/dependent. I never wanted anything form my folks but none-the-less they did help me out a couple of times when I was busted for felony possession of cannabis and was unable to bail myself out of jail. Even though you and I view the world and our experiences thru dramatically different lenses, I learn so much from reading your story. Thank you and keep up the good work.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wish I’d learned more self reliance as a kid. To this day, my first reaction is panic whenever a renter calls with something that needs to be addressed. And I’ve been a landlord for 15 years! That self-doubt in business and money matters still runs deep, despite all present evidence to the contrary.

LikeLike

Looking forward to the next chapter. We will be leaving for WI (Coon Valley) arriving on the 21st. Can’t wait – we visit all our old places and do a lot of our walks in La Crosse on the south side.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I hope you have a great time during your return to La Crosse, Judy. And thanks, as always, for your continued interest in this memoir manuscript! Wishing you all the best.

LikeLike

Another truthful read ! It’s a shame things had to get so ugly but I do understand… I’m just glad you are happy now with your like!

LikeLike