Losing You One Way or Another

These days, there are a pair of fully decked-out city softball parks abutting the open space south of Harry Spence Elementary, with bleachers, backstops, and home run fences. Tavern league teams use them all summer long, sometimes late into the evening, and the glow thrown up from the field lights can be seen all over the far south-side.

Sometimes, in the light of day, I park in the empty gravel lot for a while to look out over the fields and blacktop areas of Spence, the recreational spaces where I spent recess over the span of seven years. I’m not usually parked there for long. But I visit the place often enough, just to sit in silence in my car, to think or meditate, to reminisce, sometimes to heal. Among the many sacred spots along my life’s course, the existential or geographical spaces that Joseph Campbell referred to as “bliss stations,” that school site is possibly the most beloved.

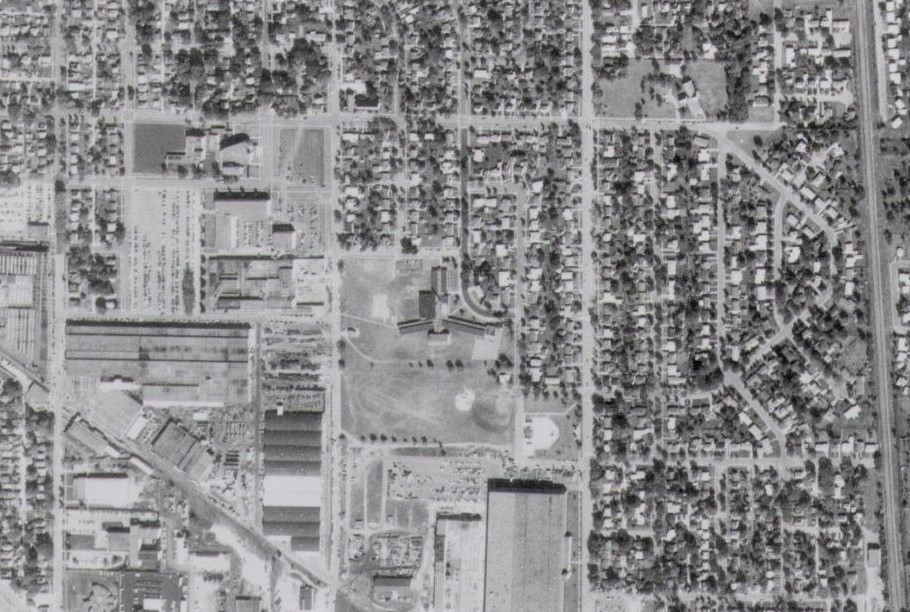

I have an aerial photograph, taken in 1974, that depicts the portion of La Crosse surrounding Harry Spence. The school building itself is near the center of the image, its three wings reaching out to the north, east, and west like the whorls of a spiral galaxy that, if extended, would encompass the collection of post-World War II neighborhoods it centers.

This last comparison is apt, for Spence Elementary was completed in 1953, just in time to welcome the first fruits of the postwar baby boom. For most of us kids, Spence was the hub of common activity—indeed the place where we spent our daytime hours nine months out of every year. The exceptions were the kids from Catholic families whose parents sent them to St. Thomas More, a parish and parochial school that sprang up around the same time and was less than two blocks away.

The neighborhoods surrounding these schools and feeding them with students reflected all La Crosse at that time in the fact that they were, outside a handful of exceptions, populated exclusively by white people. It is notably different today, but during my years at Spence, there wasn’t a single African American kid in the student body. I know you knew of one black family, the Mosses, that had lived on the north-side and included several generations of barbers.

There were almost certainly kids with American Indian blood in the public-school system, but I can’t come up with any solid memories of them at Spence. And the only Asian kid who springs to mind had only arrived with his family from Saigon around 1973, when I was in fifth grade. After years of watching the Vietnam War on the CBS News with Walter Cronkite, I’d thought it fascinating that we now had in our very school a person from that troubled area. One day on the playground, I asked him if he’d seen any of the fighting—I think I asked specifically if he’d seen any people killed. He was a quiet kid, nice, decent at speaking English, but he looked down at the blacktop that day and mumbled that he’d rather not talk about it. Not quite getting the signal, I persisted, requesting that he say something in Vietnamese. He smiled shyly, gave me the word for “corn,” then wandered off. I think that’s the only interaction I had with him.

Although the neighborhoods around Harry Spence Elementary lacked any degree of racial diversity, they did reflect the class and status transformations that characterized postwar white America. The Roosevelt-era GI Bill provided some twelve million veterans not only with low-interest loans toward home purchases, but it also opened the door to opportunity by granting veterans the funding to pursue college degrees.

The other transformative factor then was the economic surge that followed the close of hostilities in Europe and the Pacific. With wartime controls and rationing finally over, Americans went on an unprecedented shopping spree. Likewise, an industrial sector unleashed from limiting (but still lucrative) wartime production hit the ground running, ensuring good-paying, largely union-backed employment that, for the first time in American history, lifted the laboring classes into the realm of wider affordability. In short, the skilled working population became part of a middle class that had previously only included professionals.

Our neighborhood near Harry Spence embodied this new socio-economic reality. You and Mom owned your own businesses, and our neighbors included, among others, fellow sole proprietors, factory workers, a few college professors and public-school teachers, a Lutheran minister whose kids were my friends, managerial types, clerks, a home-improvement pro who traveled the world with his wife and had a museum-worthy collection of seashells, a street department man, a guy who worked for the newspaper and chiseled in quarries for rocks and fossils as a hobby, and a liquor distributor and his wife with whom you and Mom met frequently for cocktails. The kids I grew up with, both in my immediate neighborhood and during those early years of elementary school, were the offspring of this late-midcentury hodge-podge.

I entered kindergarten at Harry Spence in 1968. Mom dropped me off on her way to work. I don’t remember being afraid about starting school. A photo she took that day shows me standing, expressionless, outside the school building with the other new arrivals. I’m wearing a dark-blue cardigan sweater with a nametag pinned to it. Though I wasn’t doing it yet, over the coming years I would develop a nervous oral habit of chewing holes in my sweaters and shirt collars, as well as eating paper, gnawing on pencils and erasers (and even the metal ferrule that held the eraser). But embarking upon my academic career at Harry Spence on that fall day, at least, I was cool as a cucumber.

The main thing I recall from that day is all of us sitting around a series of long tables in the classroom, and the boy right across from me was having a rough go of it. He bawled and howled as his dad tried to force him to stay in his seat. I don’t remember any other parents being in the classroom, so it must’ve been the culmination of an ongoing struggle between home and school. In the middle of this hurly-burly, the boy gasped suddenly and let loose a tremendous sneeze, blowing a major glob of snot onto the table. He turned out okay in the end, but that was his first day, and it was a bad one. I don’t know if any of my former classmates remember it, but that snot explosion remains clear in my head as though it happened yesterday.

Another memory, this one from later in the school year, has me sitting in a little circle with three friends during free time one morning. The snot-blowing boy from the first day is one of them. I’m telling them about something that happened at home just before school.

You had been out the night before and came home late. I’d been asleep, but I woke when I heard you clomping about downstairs. Suddenly there was a crashing, broken-glassy sound. At first, I thought you might’ve fallen and gotten hurt, but then you let go a maniacal laugh. There was no one downstairs to laugh with you, and that fact only made the outburst more eerie, and not at all funny. Turns out, you had knocked over and broken a table lamp.

The next morning, I woke to the sound of mom yelling at you. My upstairs bedroom door was open, and you two were standing just outside, in the hallway. I got up and stood in the doorway, a little inside my room.

Mom wasn’t yelling about the broken lamp. She was demanding to know who you’d been with. Who was she? Over and over she repeated the question. I don’t know if I cried for you two to stop fighting. I might have. Or maybe I just stood there. Mom was hysterical.

Suddenly you swung and slapped her hard across her face. You may have done it a second time. I don’t recall if you acknowledged that I was standing there. I don’t know if you stopped when you saw me, or even if you saw me, or whether you cared that I was there. I don’t know if either of you offered me comfort. And I don’t know if any of that would’ve made a difference, because you’d already hit her.

I don’t recall which one of you dropped me off at Harry Spence that morning, or whether there were any “that’s just something people do sometimes” explanations on the way. Maybe there was only silence. I don’t think I would’ve brought it up myself.

All I remember clearly is what transpired later: me sitting in that little circle in the kindergarten room with the snot-blowing boy and the two others, telling them that my dad had hit my mom just before school. That is memorable enough, but what is striking to me today is that I wasn’t crying or even especially distressed. I just said it matter-of-factly.

Was that the first time you’d hit her? It’s the only time I recall seeing you do it, though I know there were other times, after that. Mom had bruises sometimes and the explanations never really shook out as being convincing. You’d been married fifteen years by the time I was born. And according to Mom’s sister, you two were enmeshed in a hellish argument on the way to your own wedding. You fought often and viciously throughout your marriage. Surely the hitting had to have gone on before that one time when I was five. Maybe many times. Probably many times. Had I witnessed other occasions of you hitting her but locked them away? Do I carry the force of other suppressed memories?

I began this chapter proclaiming Harry Spence as being a beloved station of my life. So why am I now going on about me chewing on pencils and you hitting Mom?

I guess that in the course of writing this I had wanted to focus on another side of my past for a while, the part that was all about sheer joy, creative imagination, and a belief in things not quite believable. I’d already talked about the sense of personal victory I experienced in the catch during that sixth-grade softball game. And I’d hoped to expand in this mood and mode by going into other, equally memorable tales of exhilaration or glory: Like my desire (albeit unrealized) to stage a full reenactment of the Battle of the Little Bighorn in the southwest field outside of Spence, where a slight rise in the topography would have made the perfect setting for Custer and his Seventh Cavalry to make their storied, ill-fated stand.

High energy events like these were facets of that time, normal in fact, whether imagined or actual. And the physical space of Harry Spence Elementary, that institution where I spent so many of my waking hours between the ages of five and twelve, was the place where so many of them happened. Never in my life was I so passionately involved with wonder as then, or there. So perhaps it’s not surprising that I like to touch back upon this time and place when I park in that gravel lot to sit in silence, just a few yards from the high ground of my imaginary battlefield.

But there is another side of the childhood story that also wants to show itself. So, I must address it here as well. To do otherwise would be mythologizing the past.

Truth is, I was just as much an emotional train wreck then as I am now. I was afraid of so many things that loomed outside of my little-kid ability to control, like tornados, explosions, the war in Vietnam.

But the most intimate and terrifying variables centered around you and mom.

Divorce or death: I was afraid of losing you both for a long, long time. Of course, it didn’t help that you two fought so often and so furiously, or that you yourself talked freely of the prospect of your dying. That went on a lot when I was little. Sometimes it was the last thing you’d whisper in my ear before bed. I don’t know if you did it to get attention, to prepare me for something you honestly believed was coming, or to garner some proclamation of regard.

This last was a peculiar need of yours, as I would discover later. Like the time in 1989, at the funeral of my maternal grandmother, whom we all called “Nana,” when you told me that people should verbalize their esteem for loved ones before they die, rather than in conversation with others at their funeral. The chasmic pause after you spoke made it clear that you hoped I’d fill in the blanks and say something. But by that time in our relationship, I was so deep in resentment over your persistent drunkenness that I couldn’t have brought myself to do it even if I’d wanted to. My negative response to the very thought of saying “I love you” (or anything similar) to your face was visceral. The same was true of Mom, and for much the same reason. Not that I didn’t feel it in my heart, after clearing aside the relational wreckage. It just made me cringe to say it, so I seldom did.

But it was a long road leading to that point. My best guess is that I began mourning your impending deaths somewhere around third grade. In other words, some three decades before either of you died.

And by that time, I was long past mourning you in any proper or timely fashion.

Most of that is on me, I’ll admit. I have a wild, often dark imagination that runs to the point where I lose track of what is and what isn’t. I go from zero to existential crisis in a space of seconds. Thankfully, I have a better handle on it now, thanks to medication and years of therapy. But when I was a boy, my anxious meanderings could hold me in a grip for weeks. The psychologist James Hillman might have suggested that this was my innate guiding essence, or “daimon,” preparing me for a future as a writer: a person intimately familiar with the conjuring of alternate storylines, adept at traversing the depth and breadth of emotion. I don’t discount that possibility. After all, I’ve felt the weird pull toward a life of letters like a force of nature ever since I was a little boy. Those skits I crafted as a kid, the song lyrics and poems, the dreams of sweeping drama on a school playground—these things did not come out of nowhere.

But it would be useful to have at least known something of the price tag in advance, to say nothing of having had a reassuring glimpse at the way things would eventually play out, because I spent so many of my younger years in terror, tossing through sleepless nights obsessing about you and/or Mom coming to an end one way or another. There was no way then I could or would have predicted you’d both be around: alive and still married, well into your seventies, and into my forties.

And didn’t that turn out to be a mixed bag of weirdness.

Another good read Rick. Explains a lot to me as well !

LikeLike

Had some catching up to do. Somehow had missed reading chapter 7. As always interesting. We will be leaving for WI come next month for our yearly 2 month stay. Reading your book made me want to visit our old neighborhood and the area by the college where my grandparents and great grandparents lived. All gone now but the memories still exist!

LikeLike