Work Was Everything

We often worked in silence, or at best exchanged a few words—a quietude arising out of mode rather than mood. You chewed your tongue while working. I probed the inner wall of my mouth and my gums with mine.

I still do this. I catch myself doing it when I’m raking, washing dishes, whatever. Recently, a friend posted a cell phone photo of me playing bass at an Oktoberfest gig, and the exaggerated convexity of my right cheek suggests I’m storing a wad of tobacco in there. But it’s my tongue.

You and I were smokers though, which probably explains the oral fixation of chewing and probing. I’ve been free of tobacco now for more than twenty years; you quit three months before you died. But we never took cigarette breaks when we worked. Instead, we just kept going, ciggies pressed between our respective lips, puffing away. And when we weren’t smoking, we worked our tongues.

We worked our asses off when we worked—painting interiors and exteriors for ourselves and others; pulling weeds around your barbershop building, or at your commercial rental in nearby Sparta; tarring over the leaky cracks in the flat roof of Mom’s flower shop building; scrubbing grime from brick walls with a mixture of vinegar and hot water.

Small jobs, big projects—all necessary.

Sometimes we fought when we worked, and the flash-in-the-pan Irish temper I’d inherited from Mom would clash with your crueler and more calculated anger.

One day, near the end of your life, you’d asked me to meet out back at the barbershop to pull weeds. I needed to drop my daughter Sophie off at her mom’s first, I’d told you, and would be a bit later than you’d wanted me to arrive. But I’d be there. You said okay.

“Take your time,” you said.

True to form, you showed up early and started without me, your efforts stoking the COPD that was gradually but certainly killing you.

When I arrived, you were pissed, so pissed you were in tears: yelling at me before I could even open my car door. Because of my lateness, you yelled, you’d had to push beyond your limits of breathing. My lateness might’ve been the end of you. Was I trying to kill you?

I returned fire, bellowing that you were full of shit. That you knew full well that I’d be late. The fact you’d started on your own and almost died was your own damned doing.

We went on like that for a while, bitching and swearing, and when we stopped yelling, we grabbed our trowels and gloves and ripped weeds out of cracks with silent fury for the better part of the next hour.

After we finished, it was like nothing had happened. Just another day, and another job done. See you next time.

Some five years after you died, I was painting the upstairs apartment of a duplex I’d recently purchased. Alone, up on the ladder with a tapered brush, I worked that tricky corner space between the ceiling and wall like you’d taught me. On my little CD player, Chet Baker finessed a sad trumpet phrase in Jobim’s “Portrait in Black and White.” As I slid the brush across the corner, gently twitching it back and forth to distribute the paint evenly, I caught myself pressing the tip of my tongue hard against the inside of my cheek.

For an instant I felt you in the room as well, chewing away in your own fashion.

Suddenly I was crying so hard I had to stop working. I climbed off the ladder, sat on the bare floorboards, and let it happen. I was out of breath, my face wet.

It was the first time I’d mourned you.

***

Work was everything. You learned that from Grandpa. Grandpa learned it somewhere—maybe out west in the early 1910s, maybe back in Illinois as a fatherless son making his way in Peoria or nearby Elmwood. Because of the years of secrecy and his web of untruths, Grandpa’s personal path to learning has been hard to trace and might never be documented fully. But in the end, whatever experience he drew from stuck with him, and the lesson was passed down: Work is the crucible that tests and ultimately proves a person’s legitimacy—and in his case he meant a man’s.

Money, winning personality, intelligence—none of these abstractions mattered without the undergirding of conspicuous, hard work.

As you always said, for Grandpa it was clearly a “work to eat” situation. It took precedence over all other concerns because, to him, it meant simple survival. And heaven help the fool who shirked or otherwise neglected this sacred responsibility, no matter whether the offense was intentional or, as in the case of a particular morning during your teenage years working on a section crew, accidental.

Back in the early ‘40s, there was a Greyhound bus that picked you and the other workers up every morning to take you out to the site where you’d spend the day pounding stakes and laying track. One morning, Grandma poked her head in your bedroom doorway, as usual, to make sure you were awake. And surely you seemed to be, for you sat up and talked with her for a bit.

But you were just sleep-talking, and when she turned to go back downstairs, you lay back down and slumbered on.

Your first conscious recollection that morning was a bit later, when you heard her yelling to you from downstairs, and, looking at the clock on your nightstand, you jolted up in a fright and scrambled to get ready.

“I threw on my goddamn clothes, and I ran out in the middle of the street,” you told me in a recorded interview. But the bus full of railroad workers whizzed by on its way toward the highway and out of town. You sprinted after it, shouting and waving your arms, but no one in the back of the bus saw you. It continued up the road and out of your sight, leaving you huffing and puffing and, as it turned out, missing work.

So, you walked back home and went to bed again.

At the end of the day, your dad came home from the Rubber Mills, and Grandma told him about what happened.

“Holy shit,” you exclaimed to me when you got to this part of your story. Sixty years after the fact, I could hear the fear in your voice.

Grandpa cornered you right away.

“You missed work, huh?” he said.

“Yeah, I didn’t wake up.”

He grabbed your arm with his powerful shoemaker’s hand. “You son-of-a-bitch. If you miss another day of work, I’ll go over and tell your foreman to give your fuckin’ job to some kid who wants to work!”

Workday or not, I don’t think you overslept another morning for the rest of your life.

To be sure, Grandpa’s anger, his words, and the physical intimidation stuck with you. The most impactful part, however, the life-defining kernel of meaning you took from the incident, was the importance, the necessity, of hard and dedicated work in the making of a man.

You tried to instill this ethos in me, too, I know. But just like my late-blooming athletic interest, it would be years before your efforts and hopes would bear fruit.

To put it plainly, I detested work. Or rather, I had no problem putting hours into brainstorming the makeup of a globe-spanning empire, over which I assumed autocratic control and supreme leadership of its military. I could spend the day in my bedroom crafting skits that I’d put on at school with another friend. I could invest time in the garage nailing together go-carts made of scrap wood and old strap-on roller skates that never operated as planned. Later, as a teenager, I put in hours each week practicing with my first rock band and writing songs.

But when it came to chores and errands, no thanks. And as for school, teachers always peppered my reports cards with comments that stoked your anger: “lacks self-discipline”; “attitude needs improvement”; “does not complete required work”; “lack of adequate daily preparation”; and, in perhaps the most accurate and damning description, “satisfied with mediocre achievement.”

Unlike you, who probably started doing household chores (and loving it) as a toddler, I was a lazy kid. I remember one day, probably at about ten or eleven years-old, when you’d ordered me to clean the garage, something I’d never had to do before. I was so mad about it that I probably got some unintended exercise from the vigor with which I swept the floor and stacked boxes of stuff along the walls.

Our next-door neighbor happened to be leaving his house at the time, and he poked his head in the big roll-up doorway—no doubt alerted by the sound of my grumbling and swishing about with the broom. He snickered at my obvious displeasure.

“Will you look at this!” he remarked. “I can’t say as I’ve ever seen you work before.”

“Yeah?” I shot back. “Well, I hope you never see me do it again!”

***

In 1990, at the age of twenty-seven, I quit the family flower business, and for a while it seemed as if the world teetered on the brink of collapse.

Mom had worked at My Florist since the 1940s, and she had owned it since 1960—three years before I was born. In addition to her having been an integral part of that shop, the shop was even more crucially a vital part of her. Such was her love for the place, and the labors performed therein, that she insisted on returning to work a mere three days after giving birth to me and did precisely that—turning my daytime care over to a revolving door of babysitters.

Mom’s lack of sympathy for her own postpartum medical needs (to say nothing of any maternal instincts she may have had) carried over into her management style at the shop. The story of her hasty return to work, post-me, became a cautionary tale she shared with employees (me included) over the rest of her life. It became one of her most frequent boasts, and she used it regularly to shame anyone who tried to take too many sick days from the shop or, horror of horrors, to ask for extra time off for newborn care. It was said around the shop, with equal measures of jest and gravity, that during the trifecta of florist boom seasons—Christmas, Valentine’s Day, and Mothers’ Day—we would need a signed note from the county coroner to get a day off. And, speaking of mortality, Mom once even chided a longtime, loyal designer with the conclusion that the woman’s terminally-ill father—for whom the employee had taken time off to look after—wasn’t dying fast enough.

The flower shop also happened to be the place where you and Mom met back in 1947. You had stopped in one day to buy flowers for a girlfriend; at the same time, Mom was working there as a clerk and was engaged to someone. But the universe had other plans, as it often does, and soon after that your girlfriend and Mom’s fiancé were both out of the picture.

I had worked at the shop on an as-needed basis since junior high, unpacking boxes of pottery and wrapping winter deliveries. In 1983, I started delivering at My Florist, but the very next year I was “promoted” to a full-time job as a designer. Not coincidentally, this occurred just after my girlfriend (and future first wife) became pregnant with Dylan.

Over the next seven years, we’d all pretty much assumed that I would take over the shop someday, even though I had next to no business sense and had yet to discover and cultivate a comprehensive (as opposed to selective) work ethic. Nevertheless, during that span of time, all things seemed secure looking forward. You and mom could rest comfortably in the assumption that I’d follow in the family footsteps. Meanwhile, I could continue to pay lip service to the idea (and some days believe it) while drawing a paycheck I didn’t really deserve, considering that I was patently lazy, non-punctual, and, for the first five of those seven years, routinely stoned out of my gourd. My usual morning cure for hangover in those days was a few bong hits at the trailer I shared with my first wife and baby. And since I was an every-night drinker, my days at the flower shop back then always started out high and stayed that way with frequent boosts, whether in the upstairs restroom or during any blessed opportunities I might get to run an errand in my car.

It was common knowledge around the shop that I was using at work (except to Mom, who always seemed to suspect something but nevertheless chose to ignore the obvious, instead naively questioning the other designers why I was still hungry after having just returned from lunch). I oversaw the buying of plants at the shop in those days, so I spent a lot of time getting high and snorting coke with the wholesaler in the back of his truck too. I even tripped occasionally during business hours. In one memorable psychedelic instance when I was still a delivery boy, I spent the day on psilocybin. In my addled mind, I was an agent of joy, spreading happiness to the fortunate folks receiving flowers. And I’m sure that my gaping eyes and half-crazed grin were memorable to people who opened their front doors to me that afternoon.

My work ethic didn’t improve much after I sobered up, at least not at first. Working at the flower shop was an easy way out of taking responsibility for my future. I was the consummate owner’s kid: privileged, lazy, and clearly throwing off a vibe that the rules did not apply to me. As I ticked off the months without chemical enhancement, though, I began to recognize the charade through which I’d been living.

There was a general awakening to my own brain potential, and a damning awareness that I’d been skirting the responsibility of nurturing it. It began to chafe that so many of my friends had not only finished college by then (unlike me, who dropped out in 1983 after having neglected to show up for three of my finals), but some of them had since gotten their master’s degrees. A few were even enrolled in doctoral programs. I’d known these people for most of my life by that time. They were smart, I could concede, but I also knew that I was at least as smart as the best of them. Yet here I was: fucking the duck in a job that I hated, collecting a weekly paycheck not because I earned it, but because my status as heir to the throne ensured that I’d never be fired, no matter how pathetic my performance might have been.

For nearly a decade, I’d been living on past accomplishments: flaunting a knowledge base I had gleaned from books I read as a kid, drawing on experiences I’d had back in the days when I truly was interested in learning new things. It’s no wonder I often felt like a poser whenever talking heady topics with people who were active learners, always coming away relieved they hadn’t sussed out my deficiencies. No wonder I used my ability to excel at the game of Trivial Pursuit as a validation of my intellect—with no conscious recognition of the irony that represented.

These realizations never came by way of some Cecil B. DeMille-worthy, gnostic flashes of insight, though. No flaming chariots or singing angels from on high. Rather, they came about gradually but unmistakably during the first few years of my sobriety.

The insights sometimes came in odd and surprising ways. For one thing, I began to notice signs along my existential path: subtle physical hints at the precise moment when I was pondering a sticky issue that left me with a sense of resolve that my hunch about that issue was correct. Spying a single, perfect bird feather on the ground in front of me as I walked somewhere was one frequent recurring sign. Or noticing a random word on a billboard at the very same instant that someone on the car radio said it.

I know, stuff like this can easily be written off as coincidence or explained away as a heightened awareness that comes from quitting drink and drugs. And I’ll be the first to admit it may have just been me grasping at straws.

But it happened often enough at critical junctures to have been convincing. So, I went with it. And to this day, whenever my ducks of spirituality maintenance are in a row—that is, when I’m meditating regularly, exercising, perhaps in a writing habit, and when I’m taking time to simply be silent, still, and to be—those signs begin to present themselves again. And they are always reassuring when they do; and in their peculiar ways, they are always right.

During that early time off the bottle, and even more so after I gave up drugs, I also began to find instruction in passages from books and spoken lines in movies. In the late ‘80s, a good friend of mine named Cathy, who was further along the path of self-awareness, turned me on to a book by Richard Bach, titled, Illusions: The Adventures of a Reluctant Messiah—a simply told but deep fictional story of an itinerant biplane pilot who comes under the tutelage of an enlightened young man and fellow barnstormer, Donald Shimoda.

It was one of those perfect intersections of need, opportunity, and information that are nothing short of life altering. At least it was for me when I first encountered it in 1987. I have reread Illusions since that time, and the effect has never been quite the same as it was after that first read. But that does not diminish its importance or its place in my life.

The book became available to me at a time when I most needed to learn its lessons. My first wife had moved out at the very beginning of that year. I had only been off alcohol a short while. I was facing the legal and financial consequences of a drunk driving conviction. And ironically, after having lived so much of my childhood in fear of you and Mom divorcing, something that never came about, I was now facing that very end in my own marriage.

I felt better overall, especially physically, but I was still lost in so many ways, too. To my surprise, life seemed off in early sobriety, like I should have been getting something that I wasn’t quite experiencing yet. I’ve come across that roadblock at other times since then, and I’ve come to believe it’s a common letdown for addicts and codependents, whether or not we’re recovering: Time and again, I fall for the self-delusional belief, forged in moments of despair, that, if I can only accomplish or access this one particular thing—a new job, a significant other, financial windfall, sobriety, whatever—then all of life’s disparate pieces will come together at last, and would last forever.

Nice in theory, but in real life it’s about as effective as chasing rainbows. To be sure, quitting drinking had swept more than a few problematic crumbs off the table for me. But there were still plenty more scattered about. And the longer I stayed sober, the more this became apparent.

Taken along with other sources of learning, Bach’s book was indispensable in demonstrating that so much of what I was running up against at that time was colored by my limited self-belief. If you spend enough time as a drunk, with a very public reputation for being a drunk and all the ignominy that entails, you are not left with great reserves of confidence to carry into a newly sober life. Reading Illusions, I was especially drawn to the many aphorisms that peppered the body of the book, pithy nuggets plucked from a how-to handbook for “advanced souls” that Shimoda carried with him.

For example: “There is no such thing as a problem without a gift for you in its hands. You seek problems because you need their gifts.” That one taught me that the incompleteness I was experiencing, to say nothing of the lingering negative consequences of my recent drinking history (losing my license, big legal fees, impending divorce), could be viewed as necessary bumps along the way to a better existence. And, just perhaps, my soul (or life energy, or better angels, or whatever) had drawn me to these obstacles for a purpose.

After all, we talk of willful self-sabotage all the time as an innate force in people’s lives. Why can’t the direct opposite be just as available?

“Argue for your limitations, and sure enough, they’re yours” underscored the futility of excuses, blaming, and of self-pity. And on the flip side, it suggested that if I were only to push through (or simply refuse to believe in) my limited and limiting assumptions, an entirely new reality could open out. In a similar vein, but even more powerful and affirming than the others, was my favorite aphorism:

“Every person, all the events of your life, are there because you have drawn them there. What you choose to do with them is up to you.”

That put it plainly. Change was within my power.

But what form, or forms, would change take?

***

One day, while standing at my work-table at the flower shop in early 1990, doing just what I had done every weekday for the previous six years, I set down my knife suddenly and remarked:

“There’s gotta be more to it than this.”

A hush fell over the room. Even Mom was silent. And I’m still not sure whether the other designers were trying to piece together the meaning of what I’d just said, or maybe applying my observation to their own lives. Either way, it was a weighty moment. For I had just said it: I’d acknowledged, with concision, the emptiness that my awakening through sobriety had made plain. What’s more, I uttered these words in the very physical (and existential) space where I’d come to feel it most.

From then, it was only a matter of time.

Not that I wasn’t already on the way, especially intellectually. Rather than poring over the same books I’d read and reread for years, for example, I was now venturing out, digesting new sources like the Bach novel, books on history and current politics, books that touched on aspects of Buddhism and Native American spirituality.

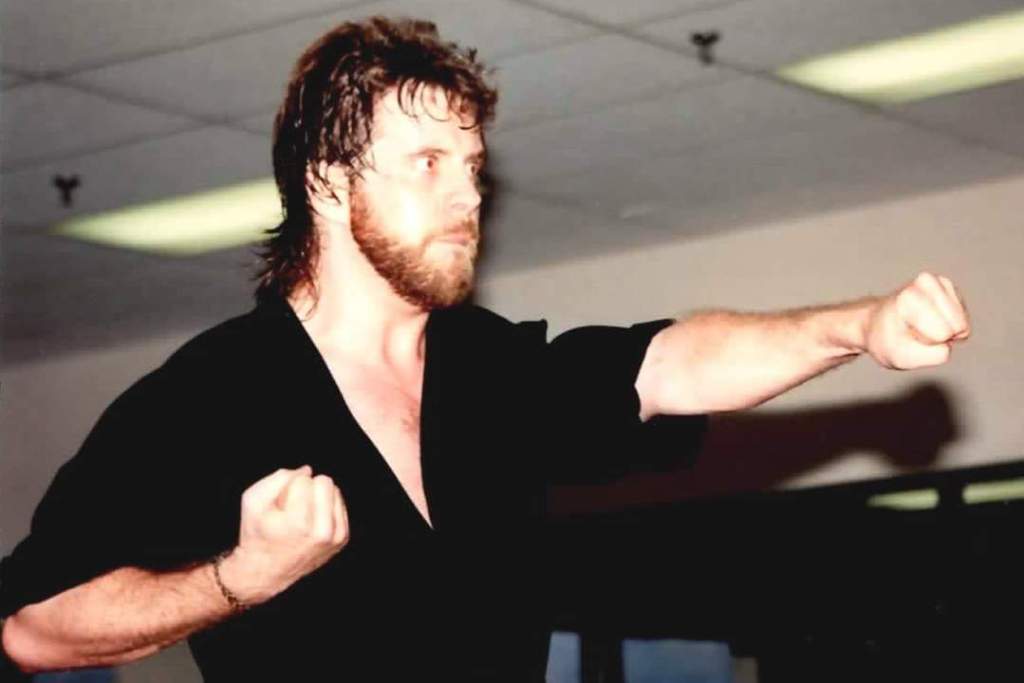

In short, I’d begun to explore new paths of thought, belief, and even physical expression. Six months into sobriety, I joined a local karate studio and embarked on a journey of study in the martial arts that would continue over the next decade, in four styles and three different cities where I would come to live. In the spring of 1989, while wandering through the concourse of the Met Center auditorium in Bloomington, Minnesota between sets at a Grateful Dead show, I stopped at a Greenpeace booth and picked up some pamphlets. This was in the immediate wake of the Exxon Valdez oil spill (the graphic footage of that ecological tragedy was all over the news), and after reading through the material back at my seat before the start of the second set, I decided then and there to invest myself in some way toward this cause. That kicked off a flurry of political writing and active involvement in the environmental movement.

And speaking of the written word, I began taking occasional creative writing classes offered to the public at the local tech college during the late 80s. The fiction and non-fiction pieces I put out in those classes were far from satisfactory, I now realize. Pulling that stuff out of the storage boxes and perusing them these days makes me cringe—clearly, I had yet to discover the beauty and immense satisfaction to be found in judicious revision. But it was a start.

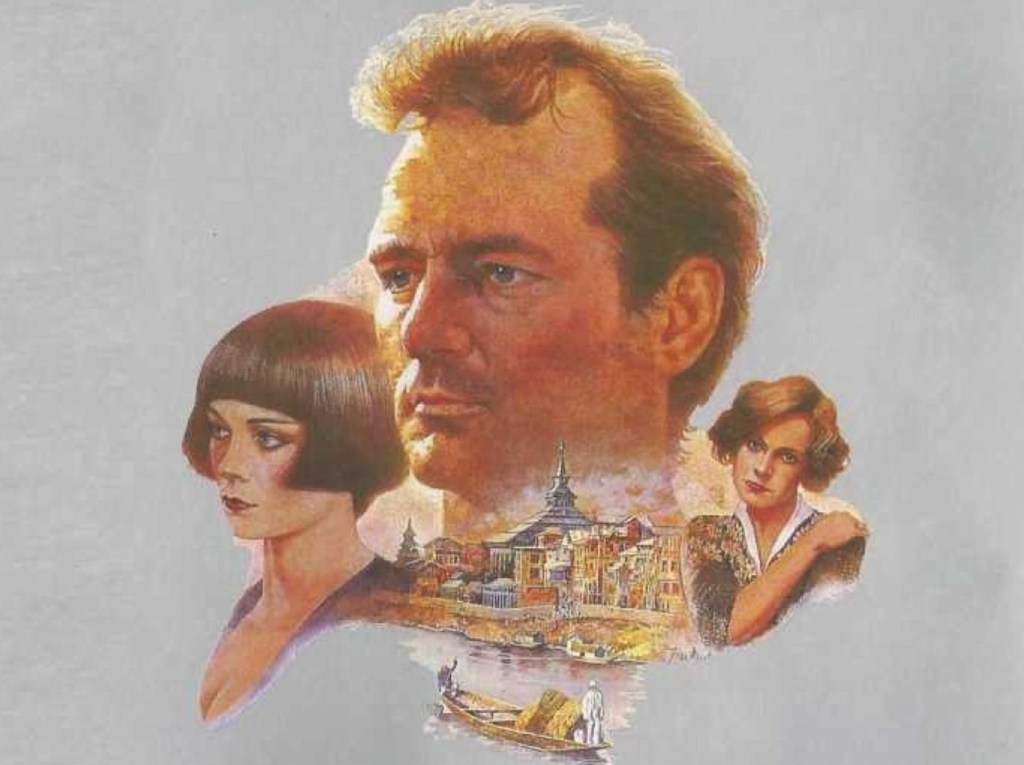

One day in early 1990, I was browsing in the video store when I came upon a copy of a 1984 movie with Bill Murray, The Razor’s Edge, based on the W. Somerset Maugham novel of the same title. I didn’t know it then, but it had flopped in theaters when it came out, and the critical reception was so negative it reportedly triggered a deep depression in Murray, so severe that he wouldn’t make another film for the next four years. I don’t think knowing about the negative reviews would’ve made a difference to me, though. My opinions often run counter to those of critics. Besides, I was intrigued by the synopsis: A young man, haunted by his war experience and disillusioned with the prospect of a comfortable but conventional life awaiting him back home in Illinois, sets off instead on a journey of self-discovery and the search for meaning.

I rented the movie, went home, and popped it into the VCR. The movie begins with a gorgeous, sweeping orchestral overture as the scene opens on an early-twentieth-century Independence Day celebration in a Lake Forest, Illinois park, where a fundraiser for the American Ambulance Field Service is underway. The First World War is ongoing in Europe, but up until then the United States has avoided entry. Nevertheless, the organization seeks to entice recruits for needed work in battle-torn France, and Larry Darrell (played by Murray) is one of two young college graduate volunteers about to leave for service as drivers. The overture and the historical setting were more than enough to grab my attention, so I settled in to watch the rest.

One scene, not quite halfway through, is set in a working-class restaurant in Paris, where Larry and his long-suffering fiancée, Isabel, are having dinner. Larry had put their engagement on hold for months now to travel the world, shake his wartime trauma, and figure out who he is and what he’s meant to do. The two are arguing, and Isabel insists that he return to Illinois, get a regular job, and that they marry as planned.

At that moment, an exasperated Larry exclaims:

“Look, I got a second chance at life. I am not gonna waste it on a big house, a new car every year, and a bunch of friends who want a big house and a new car every year! I can’t turn back now.”

I stared at the TV screen, my mouth agape. Larry’s statement, word for word, summed up my own life.

Sobriety had given me a second chance at life. And not only that, it awakened a sense of intellectual curiosity and spiritual awareness. Clearly, these little hints I’d been receiving from the universe about remaining in a job I did not like, a job taken and retained out of convenience, ought to be acted upon. Something else out there awaited me. It was a bigger, better future, and it would suit me in genuine and critical ways.

I had to leave the flower shop, and soon. I felt the urgency like never before. So, I did.

Holy shit.

This wasn’t the first (or the last) time I left a job with no backup plan. In the early 80s, I’d resigned from a job at a halfway house that was run by a local hospital, with no further prospects in mind, after I put my fist through the living room wall during a temper tantrum. It seemed like a logical next step; and never, I think, in the history of that hospital was a resignation letter accepted as fast as mine was. I would leave several other jobs in a huff later, too, again without first securing new employment.

Quitting My Florist was different. I didn’t consider the implications properly at the time, being dead set on breaking away ever since being emboldened by those words Larry Darrell had uttered in The Razor’s Edge.

But now—after having been a parent myself for nearly four decades—I better understand the impact my leaving had on you and Mom. It was a legacy shattering, personal hit.

You were counting on me to carry on for Mom eventually, and despite my on-and-off enthusiasm, I never once came out with a firm rejection of the possibility, nor even muddied the waters of surety by expressing any doubt to you.

My quitting came as a sucker punch, and you both reacted with your own flurries of counterpunches. I think it was the first time you ever threatened to disown me. Mom could barely bring herself to look at me at first, much less to speak with me.

You took a different tack, calling me often during that first week or two to berate me—insisting on one occasion that I’d spent my life treating you both “like shit” and even, just before slamming down the receiver, ragefully (and tearfully) demanding, of all things, that I “get a goddamn haircut.”

I was twenty-seven years old then, a grown man with a child of my own. Nevertheless, I dutifully went and had my hair chopped, just to appease you (in other words, to make the shouting stop).

During those years, I’d worn my hair long. I was in a rock band, and I looked the part. But cut it I did, that very same day, pleading with the stylist to retain as much of the length as she could. The unfortunate result was a ridiculous, pageboy cut. Playing a gig in a distant town later that weekend, one of our regular audience members giggled when she saw me showing up like that, referring to me as “Prince Valiant” throughout the night. I was pissed. And I made a vow that evening to never again give in to your demands on matters of hair length—a vow that I kept for the remainder of your life.

Looking back today, I see that I should have taken that brief spate of strength and expanded my vow to include all instances of knuckling under to your personal power. It would have been brutally difficult, and I’d have paid the price for it many, many times, but it might have set a lasting, healthier tone early on and leveled the playing field of our relationship.

Unfortunately, at the time it was not to be. I lacked the resolve, and without a doubt I was still petrified by the prospect of inciting your anger, wary of the Damoclean sword of rejection you had suspended over me.

There would be many more years of capitulation ahead.

***

Over those first months after quitting the flower shop, I played weekend gigs with my band. It was the first and only time I’ve lived entirely off musician’s pay. It wasn’t much, but it kept me in groceries. The band developed an especial bond, too, a family-like vibe we shared among ourselves and our closest friends. We hung out a lot together, wrote music and poetry. I developed an enthusiasm for Zen Buddhism around then, too, really getting in touch with living in the moment, probably for the first time since I was a child, when it had come naturally. I cooked big dinners at my home in Onalaska, with sandalwood incense sticks burning, a pot of coffee always handy or a kettle of ginseng tea on the boil. Some of the members and friends even joined me in political activism.

It was a heady summer in 1990, one of the best for me. I felt as though I was on the brink of coming into my own, independent space as a person, perhaps even as a man. Some of the activities I’d been pursuing in recent years—like martial arts, writing, and activism—had helped in this respect.

These awakenings of conscience were a big factor in leading me toward returning to college at UW-La Crosse, which I also did that summer, thus concluding my long, intellectually dry, seven-year “semester off.”

It wasn’t easy. I’d been officially declared ineligible to return. (I can still picture this proscription rubber-stamped like a scarlet letter on my transcripts.) Fortunately, though, you had some barbershop customers who worked in the admissions office across the street and were able to arrange for me to reapply, though I never asked you to do so. It is another of the many wacky examples of paradox in our codependent relationship that spanned the forty-three years that our lives ran parallel. You could be a real asshole when some issue exploded between us—like my abandoning the family business, for instance. And I was no different. But then a week, a day, or even a few hours later, you might come through with almost saintly beneficence, as though nothing at all had happened. Good comes from odd sources and circuitous paths, I’ve found, and I realize today (far too late to admit it to your face) that, among the myriad dysfunctional traits I took on, and often embodied, as your son, I also learned from your example the meaning and practice of generosity.

Thanks to your help, and to my great surprise, UW-La Crosse accepted me, and I returned on a probationary basis for the 1990 summer session. The registrar, when signing off on my choice of classes for that beginning session, glanced me over and implored me, simply, to get A’s. His advice caused me to shudder, so daunting the prospect seemed at the time. But I nodded, thanked him, and set off on my new adventure.

There is a potent line from Shakespeare’s Henry V, in which the Duke of Exeter chides the Dauphin, the French crown prince, for grossly underestimating the kingly capacities of this newest English monarch. “And, be assured,” Exeter warns, “you’ll find a difference, as we his subjects have in wonder found, between the promise of his greener days and these he masters now.” In later years, I would draw from this line whenever I needed to build myself up for some considerable task at hand. In fact, I often do the same today. But I did not know of the line that summer when I reentered college as a twenty-seven-year-old; and even if I had, there was little cause for me to have applied it or its message to myself.

For I still carried the onus of my previous academic failures. Of course, I wanted to believe that I could succeed as a college student, being now older and hopefully more mature, but I could not be certain that I would. In the back of my mind there remained the less-than-promising example of that irresponsible student from the early ‘80s, to say nothing of my more recent persona: the shiftless, privileged owner’s kid from My Florist.

And I wasn’t alone. Given my history, not too many people at the time would have cast bets on my success going forward. Why should I have?

And, by the way, what did you think? I know the details along the timeline—how it all played out: I quit the family business. You exploded and harassed me over it. Some months later, I decided to give college another go. You did what you could to make possible my reentry. I reentered.

But surely you had to have harbored misgivings, if not outright prejudices, about my decision. After all, I’d failed once before, due to what could be called a constitutional lack of self-discipline. How could this latest attempt at higher learning roll out any differently than the first?

Moreover, from a practical standpoint, the flower shop had at least held out the promise of a future: guaranteed employment, continued income, eventual ownership. At the end of the day, you could possibly overlook my faults and incapacities as an employee, distasteful though they were, if only to draw comfort from the assurance that you wouldn’t have to worry about me becoming insolvent or a public charge.

On the other hand, college, for all the advantages it may bestow in theory, did not guarantee anything—especially for me: a person interested in the humanities. At the time, I was reentering as an English major, having dropped my former focus of political science. My main aspiration now was to become a better writer. Well, not simply better. In keeping with my knack for hubris, it was more inflated than that: Truth was I intended to become a great writer. Yes, the child who would be emperor had grown up. Now, he was a wannabe Hemingway or Fitzgerald. He’d exchanged his laurels and scepter for a Brother word processor and was ready to join the pantheon of literary giants.

I’ll never forget the look on your face the day I stood in your barbershop across the street from campus and told you my plans.

But setting aside the case for my career aspirations (or delusions), I suspect you were also wary of the person I might become in the course of pursuing a college degree. Your shop, being close as it was to the university, made it a convenient stop for campus administrators and professors. Some of them even became friends of yours—you met monthly for poker games with a handful of them for years. And many, many more of them were regular customers.

You certainly enjoyed their business, and often too their company. But you also harbored a self-conscious awareness of the wall of disparity that higher education placed between you and them—namely, they’d had it and you hadn’t. Of course, you weren’t alone by any stretch. Social scientists and historians have long recognized the entrenchment of anti-intellectualism in American society, particularly among the working- and lower-middle-classes. The GI Bill helped to narrow that divide since the 1940s by democratizing access to college education (at least for poor whites) but that underlying sense of wariness, and often resentment, has remained. And it still runs deep today.

It was years since you, and Grandpa before you, had toiled for the railroad, but that simmering hostility toward people of a perceived higher station carried forward into your daily life in middle-age, cutting hair across the street from a state university. In this way, the professors with whom you had daily contact as customers became your latter-day “white hats.” You’d listen as they talked, with their erudite phrases and sophisticated understanding of the world. And it rankled you. Back at home, after work, you’d cut them down to size, referring to some of them as “educated idiots” who could sit in a classroom all day and wax philosophical but “didn’t know enough to show up on time for a goddamn haircut.”

The thought of me becoming one of these guys left you uneasy, I suspect. You never could abide pontificators. Not that I didn’t exhibit that character trait already. For me, it is the behavioral manifestation of a need to explain, to demonstrate knowledge of something, to not feel left out of a heady discussion. Sometimes I just want to fill an uncomfortable space of silence. On other occasions, I’m passionately interested in something and I want to share my perspective.

But just as often, and as the guidance counselor way back at Harry Spence Elementary made clear, “talking smart” was simply a way to attract attention.

Paradoxically, one of the truly profound things I discovered during that initial summer session and first full semester of my 1990 return to college was how much I didn’t know. I half expected this, of course. I had learned several years earlier in the martial arts to both anticipate and enjoy a lengthy process of filling an empty vessel. In this way, learning, even hard and painful learning, ultimately yields pleasure because there is always more to look forward to, more to build upon.

And there were loose ends to tie up as well: I had failed several classes during my first attempt at college in the early 80s (namely, the skipped finals), and I’d also incurred an incomplete. In this latter case, a lecture class on social stratification, I’d neglected to attend it for weeks toward the semester’s end and didn’t turn in a crucial paper either. When I finally did show up, on the last day, I proffered the excuse that I had suffered a nervous breakdown from an LSD flashback—a complete bullshit story.

I’d gambled that the sociology professor, an old sixties radical, would sympathize with, or at least understand, a justification like that to have missed a lengthy block of his classes. Fat chance. I’m sure the man had heard a whole range of excuses during his time, but the unmistakable “are you kidding me?” look he gave made it clear he hadn’t heard that one. He just rolled his eyes, shook his head, and walked off without a word.

Seven years later, I sat in his office discussing the possibility of completing (which also meant starting) that long-tardy paper and turning my incomplete into an actual grade. I don’t know if he remembered the flashback fabrication I’d told. If he did, he didn’t bring it up, and I was glad for it. I proposed as a topic the stratification of women in American society. He agreed, and I set out to dazzle him with what I presumed would be a masterwork of feminist theory.

The resulting product, more a leftwing screed than a proper term paper, was devoid of citations and heavy on mostly unsubstantiated opinions. Hard to believe, but up to that point I was unaware of the necessity of formal documentation in a serious research paper. It was the last time I’d make that mistake. In fact, over the next three years, and two more after that in graduate school, I would come to love documentary research and writing, and I’d master the process and style of citation. But this first effort did not leave me (or anyone else) confident in my prospects as a college student. The professor changed my final grade in the class from an incomplete to a C.

Under the circumstances, I deserved no better. It was a humbling first lesson in scholarly responsibility. But that’s what I was there for. The hard lessons would continue. But the vessel began to fill, too.

Over that first year back, I retook the three classes I’d failed in the spring of 1983: English composition; women’s studies; and an anthropology course, “Religion and Magic.” Fully aware that I’d get only half credit for whatever grade I earned in them now, I worked my ass off and got A’s, which showed up on my final reckoning as C’s. I hated the onus of getting C’s for A work, but that was the deal, and I took it. More humble pie, but I needed it. Besides, if nothing else, it helped to tidy up my grade point average.

By this time, I’d also dropped the English major in favor of history, after hearing a dynamite guest lecture on women and law by a well-loved professor from that department in my women’s studies class. It made sense academically for me to switch. For one thing, the class descriptions in the history department looked more interesting. Plus, I’d come to realize that a formal study of history better fitted me as a person. Time is how I think: I’m surprised I’d never put that together before in terms of setting my academic course. Besides, the university now offered an expository writing minor out of the English department, so I declared for that as well. It was really the best of both worlds.

One especially important thing I learned during my return to UW-La Crosse was that I no longer had to believe in the limitations I had held to that were based on past performance, or more importantly what I’d been told about my past performance. For example, ever since elementary school, I’d had a visceral distaste for math. I don’t know precisely how it started, but it was always with me. I remember admitting to my second-grade teacher that, whenever she told us to take out our math books in class, I wanted to scream. Naturally, my grades reflected that distaste throughout my young life. While I was always in the top groups for reading at Harry Spence, and I excelled at social studies and history, I was typically in the middle- or low-performance groups for math.

You yourself always had an affection for mathematics, or at least you recognized its importance. Though I think in your case the act of ciphering was a natural trait, rather than learned. You were not a stellar performer in formal classwork either. Still, I always sensed your disappointment in the math grades that I got over the years (or, in keeping with your antiquated terminology, my “marks”). Being who you were (a business owner and landlord), and who you were to become someday (a successful investor), I think you knew in your gut that a mastery of numbers might someday be important or useful for me too. So, to bring this mastery about, you set me up with several tutors over the years. I remember you dropping me off on weekends at some professor’s house near campus when I was in fourth grade and my report card revealed a troubling deficiency. He was probably a customer of yours. Another year, you engaged an older neighbor kid who was a math whiz to come over in the evenings, after supper.

But none of these tutors helped to improve my school performance. The highest math grade, by far, that I received back then was a B-minus in geometry in the tenth grade. And I think that is only because my spatial sense is a little more responsive, which perhaps made the class a bit more interesting. It couldn’t have been raw talent. And it wasn’t diligent study, either. Thinking back today, I’m amazed I got the grade I did. That geometry class met right after lunch, which, at that time in my life, meant I almost always came in stoned.

My decision to pursue a Bachelor of Arts degree in college meant that I didn’t have to take as much math or science as would have been the case for a B.S. But I still needed some of those credits. During my first try at college in 1981, my very first semester in fact, I’d taken what was called “college math”—basically a class for people in the humanities who only needed minimal math credit to graduate. I even did a miserable job in that one. When I returned to school after leaving the flower shop, I wasn’t planning on taking a math course again, but upon finding out that I would need to bone up in this area if I intended to take the Graduate Records Exam, which I did, I enrolled in an introduction to algebra class.

To my surprise, I loved it. Yes, it was difficult at first. That part of my brain hadn’t gotten much exercise in my life. But I did the assignments every night. I even went ahead and solved additional problems, just for the practice. It became fun for me. I faced the challenge the same way I’d face a sparring opponent in Karate: straight ahead and keep on going. At the end of the semester, I had an A.

Over the next summer session, I even took statistics. It was my junior year then, and everyone was telling me, “If you’re gonna go to grad school, take stats. You’ll need it there!” (That didn’t turn out to be the case for me. I never once used it as a graduate student, nor afterward.) Since I’d returned to school as a somewhat older young person learning to assume greater and greater responsibility, I’d taken the super-condensed summer session classes as well as the normal semester terms, typically packing a full summer load of three three-credit classes.

But I’d heard the horror stories along the way about stats: otherwise bright and motivated people failing or barely passing the dreaded course. Over that summer, I decided to play it safe. Statistics was the only class I took. That was a good thing, because the course was demanding, to say the least. But again, to my surprise, I found that I enjoyed it. The only exception was the unit on probability, which I had trouble wrapping my head around. I wonder if that is the reason gambling has never been a big draw for me. I’m guessing you would’ve done well at it, with your instinct for odds.

I devoted that summer to stats, putting eight-hour days in the student union poring over my assignments, plugging data into the Statistical Program for the Social Sciences in the computer lab. So intense was my dedication to the class that it even affected the way I thought. My left-brain was getting a workout like it had never experienced, and it was flexing its muscles, kicking sand as it were into the face of my creative, arty right side. I spent so much time with my stats textbook that I found some errors in the answer key and proved them to my instructor. I developed an affection for demographics in my historical research, and for a brief instant considered veering into demography as a course of graduate study. I began to see math manifesting physically in the everyday world, too. The distribution of cars in the parking lots of department stores became bell curves.

In short, I worked my ass off, and the yield was handsome. I’ll never forget the satisfaction of standing in the hallway after final exams with the other students, looking for my name on the grade sheet posted on the instructor’s door. There it was.

Brown: A

Mine was the highest grade in the class.

The kid from the underperformer math group in grade school had made a serious turnaround.

***

You sometimes walked across the street from the barbershop to the student union to grab lunch or to pop in for a chat with friends or customers from the university. I was there one summer morning when you did, putting in one of my marathon stats sessions. You saw me and waved. Later that afternoon, I was still plugging away when you walked through the union a second time. You stopped at my table to talk for a few minutes.

By this stage of my return to college, it was apparent that the experience would play out favorably. Despite the humbling lessons learned during that initial summer session and the first semester back, or more likely because of them, I had gone on to earn straight A’s every subsequent term, not only in history but also classes in biology, geography, English, anthropology, and four semesters of German. I’d cleaned up the mistakes of my academic past and paved the way toward graduating, which I would do, with honors, on my thirtieth birthday in 1993.

But it wasn’t just grades—although I’ll admit that my ego took the wheel an awful lot during that time. (A fair share of my drive had to do with proving something to myself and, by extension, to anyone else who might have doubted my prospects.) But the most important outcome, and the one that has lasted and continues to satisfy and motivate me to this day, was that I developed a true passion for the work of research and writing. The hours that I put in at UW-La Crosse during those three years back were collectively an expression of love. I could see that.

You recognized it too that day in the student union. I could tell by the tone of our conversation that a fundamental shift had occurred between us. To be sure, the work I did was nothing like the work you had done in your long life. But that was just a difference of mode. The substance of what we did respectively, however, or more precisely the formula, was the same: Satisfaction is to be found in the efforts put toward a job well done. Suddenly, I felt respected in a way I’d never experienced in our relationship, and in my still codependent state of mind, that respect helped to confirm my own estimation.

I had discovered a work ethic.

Hey Rick: Another great chapter. I have never used gnostic in a sentence but I am now determined to. Just as soon as I look up the meaning. I used to buy all my relationship apology flowers at My Florist. That was a significant chunk of business. At the time (88 to 90) I was working at Riverfront with “at risk” clients who did not do well playing and interfacing with others. My favorite was a young guy named Joey. He was severely disabled both cognitively and physically, but could walk if I held his arm for support. He was also non-verbal but spoke volumes with his merry dancing eyes. One day, I took him with when I went in to buy flowers. He was so excited that I started bringing him there as a community activity. He loved the smells and colors.

I got the crazy notion in my head that I would work on toilet training him. After I picked him up at his folk’s house, I would remove the diaper and put on a layer of briefs then boxers under his sweatpants. Every hour I would put him on the toilet for 10 minutes and load him up with verbal praise whenever he made a deposit. So, one day we are visiting My Florist and he is sans diaper. Must have been right before some holiday cause the place was packed. Joey liked that as well being that he was very social. We are working are way around the perimeter of the sales floor and I notice a small round turd popping out of the cuff of his sweat pants. I took a quick look around and see a trail of similar fecal bread crumbs leading from the front door right to were we were. I quickly took Joey out to the car and covered the seat and floor with newspapers that I carried for such clean-up situations then sat him in there and locked the car. Then I grabbed another big handful of newspapers and a paper bag and headed back in. There had to be 12 or 14 folks in there milling around but none of the turds had been stepped on. I got down on my hands and knees and started weaving my way in and out of all those legs. Grab the turd with the newspaper and throw it in the bag. Take another paper and rub the spot until it looked clean. Crawl to the next offering. I made it all the way thru the shop till they were all collected, and never found one poop that had been stepped on nor ever saw anyone notice me down there. I’m not sure what the karmic explanation would be for that incident. But it does remind me of something my grandpa Carnal used to say. “The person who can laugh at themselves will always be amused”. Rick ________________________________

LikeLike

OMG Rick, that was a great story! I remember you coming in, and always feeling kinda cool when you’d let me know you were there. You were always a slightly older, more worldly counterculture hero to me. You’re coming in and visiting with little old me was a badge of honor. It was also at the flower shop where you clued me in about Ken getting busted out in California.

LikeLike