Your Own Man

You grew up in a violent milieu of hardscrabble contact sports with limited padding, and that extra-athletic world of fighting with other boys singly, or doing so in groups, as you and your friends did on weekends when you’d pick fights with the farmer kids coming into the city to meet girls. That group fight thing seems to me an early 20th-century phenomenon, pure “West Side Story” stuff: an outdated mode of adolescent male behavior predating the era of kids brought up on Doctor Spock and the more progressive ideas of peace, love, and understanding. But I could be wrong. After all, your grandson Dylan also grew up in a world of physical conflict among peers during the late 1990s. So maybe I am the outlier here, with my limited experience with extra-athletic violence.

In any event, you two ran with a rough crowd. For the most part, I did not.

Thinking on this, I’m reminded how often I’ve felt like a freak of nature compared to you: Your aggressive striding through life is to me the stuff of legend, whether that meant fighting (or at least posturing violently), telling it like you saw it without any thought of repercussion or offense to another, or clawing your own way out of financial hardship through an innate acuity for business and a ruthless, gambler’s instinct for making a ton of money.

You embodied a reckless, devil-may-care attitude that I lack. Even as a kid you did. You stole things, snuck onto streetcars, knocked over outhouses. You traded punches with strangers like it was just another form of play. You worked with railroad toughs on a section crew when you were in high school. You broke a guy’s arm once during an arm-wrestling match (and forever after cautioned me against this manly form of recreation—I’m guessing more out of concern over somebody breaking my arm). You told your football coach—a local legend in his own right—to kiss your ass on at least one occasion, and later walked off the team when he got on your case about smoking during the season.

On a generational level, your youth played out along some significant historical crucibles. During the Great Depression, you watched your parents struggle day to day just to stay afloat and keep the house paid off, and then pitched in to help your family move to a cheaper place when the money ran out and they were foreclosed. You watched your dad go from railroad work to the Rubber Mills and back again. And in more desperate times of no industrial jobs, Grandpa swept floors at Archie Birnbaum’s store to settle the grocery bill or did odd work for whoever needed a hand and was willing to part with a little cash or credit to get it done.

Then there was the war. Your brother Kenneth (you always called your siblings by their formal names) shed blood in the south Pacific on two occasions, the last of which provided the “million-dollar wound” that bought his ticket home in 1944—though forever after, Ken would insist that he’d wanted to stay on and keep up the fight (in an island-hopping strategy that would, a few months later, lead to Iwo Jima, where his Fourth Marine division would incur seventy-five percent casualties). Knowing Ken, a Marine to the end, I believe that he meant it about staying on, to hell with the risk. But it was not to be, and he returned to the States, where he carried hunks of a Japanese grenade in his legs for the rest of his days, along with memories of those interminable barrages on Saipan that killed many, many buddies.

And of course, you lost your brother Raymond to the Mississippi River in 1946, not even a year after he returned from his own stint in the service. He’d enlisted in the Army on December 20, 1941, doubtless burning with desire to visit a nation’s vengeance upon Japan for their attack on Pearl Harbor. As it turned out, he wound up in England for the duration, working ground crew for a fighter squadron that dueled with German Messerschmitts.

Back home after his long haul overseas, Raymond was in the mood for celebration. On the night of his death, he went drinking with two friends across the river, at a tavern in the small town of Dresbach, Minnesota. As they were about to set off again for the Wisconsin side in the dark, the craft lurched forward when someone started the motor, and all three toppled into the water. Ray had been a good swimmer all his life, but the Mississippi is swift and unpredictable in places—fraught with undertows and freak currents. As Ray’s friends made it to the bank, they heard him call out at first that he was all right. Then, suddenly, he yelled for help, and after that there was only silence.

Searchers later found his body near the locks.

One of your great regrets is that you could not make it to Raymond’s funeral. At the time of his drowning, you were in the navy and stationed on Guam. They called you to the commander’s tent, where a Red Cross man informed you that your brother was gone.

Your last living memory of him had been from early in the war. You were fourteen. Raymond—who both you and your brother Kenneth remembered as being a tough kid, a “good fighter”—would have just turned twenty-two when he shipped out. You sat on the edge of his bed on that last day, watching him as he shaved.

How poignant: the future barber’s final glimpse of his beloved oldest brother is one of a tonsorial nature. From what you said, you developed an interest in the trade while still a boy. Did you have it then? Could this have been what sealed it for you? Did you observe Raymond’s technique as he shaved himself: how he held the straight razor in his steady, fighter’s hands, gliding the blade expertly across his foamy face without breaking skin? Did you study him the same way you later studied the heads of young men at the pool hall—memorizing the idiosyncratic contours of each skull; observing how each man’s hair laid down, or didn’t; calculating how you might improve on nature’s imperfections?

***

Sometimes the signposts for our future show up in everyday observances. You played a pivotal role in many of my early glimpses into what would, much later, become a life of historical study. Like the trip we took when I was four to see Little Bohemia, the north Wisconsin lodge that was the site of Dillinger’s dramatic escape during a botched FBI raid in 1934. Or the many American battlefields that we never failed to stop at while on vacation. And even the bits of information you shared that stuck with me, like the night before we saw Lawrence of Arabia in Minneapolis, when you sat down with me in the motel room and prepared me for the complexities of the film by explaining a little about the Turks’ role in World War I.

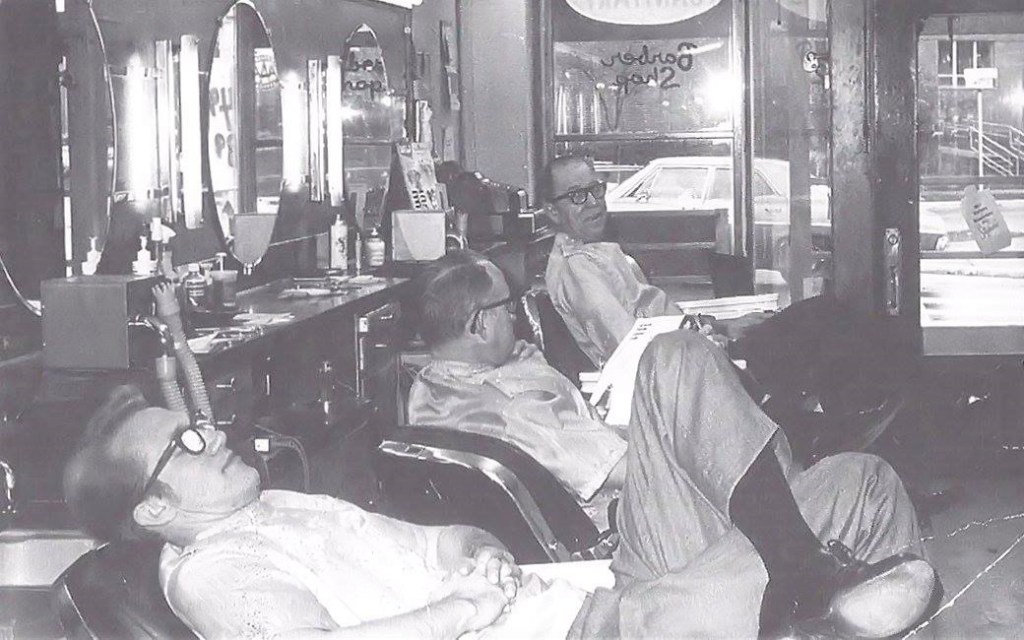

In your own life, you drew positive visceral connections from the world of the barbershop from the time you were a kid. You liked the stiff feel of the hair on the back of your own neck after a close cut. You liked the clean smell of the place, and it’s no wonder the establishment you would later come to own in south La Crosse carried what was at the time a rather common name: Sanitary Barbershop. Part of the clean smell in the air came from hair tonic, Pinaud Clubman talcum powder, and the aftershave the barber applied to the back of the neck after he’d trimmed it up with electric clippers—the latter being a cool and perfect counterpoint to the warm feel and massaging vibration of that buzzing instrument.

Your career with hair started in the navy. When you arrived on Guam in 1946, you found out there were five jobs available: one in the yeoman’s office and four spots for barbers. With navy regulations governing hair length and trimming guidelines for mustaches, someone taking up barber detail would have plenty of regular customers and gain much experience. So, you put in for it, and you sweetened your application by mentioning that you’d worked “around a barbershop” as a kid. They didn’t ask for elaboration, and you didn’t volunteer anything further. Which is good, because, in truth, you’d worked in a furniture repair place. It just so happened that the business was located next door to a barbershop.

Whether or not this extra bit of bullshit made the difference cannot be ascertained, but you ended up getting the job. Your first customer on that lonely, Pacific island was an Italian-American guy with a head of thick, curly hair—the hardest type of all to cut. Before starting, you warned the young man you weren’t sure how this was going to go, it being your first real cut. But he just shrugged and replied that it didn’t matter, he “wasn’t going anywhere” anyhow.

Turns out, the haircut went fine—it was the first of the thousands you would deliver over the next fifty years.

Back in La Crosse after your discharge, you apprenticed for the customary four years at a north-side shop. The GI Bill provided sixty-five dollars a week to live on, and the master barber you worked under contributed an extra fourteen. You joined the barber’s union and set a course for your life working in the trade. In 1952, at the age of 24, you got your master barber’s license and came to work on the south-side, at the Sanitary Barbershop on State Street, one of two four-chair shops in town. The shop was the smallest space in a three-unit brick building, and it stood just across the street from the Wisconsin State College campus. Your boss and two other barbers, all of them men in their forties, worked there too.

Just prior to taking this job, you’d been traveling every day to nearby Camp McCoy, a battalion-sized army facility, to cut hair. On your first day at Sanitary Barbershop, as you were hanging up your tools, the boss walked up to you and said, “So, you come from Camp McCoy?”

“Yeah.”

“Well,” the boss said in a voice loud enough for the other barbers to hear, “just so you know, there’ll be no Camp McCoy army haircuts here.” He meant lines of men waiting to see one barber. “Here you’re gonna have competition.”

You nodded, logging this little conversation in your formidable memory.

During this time, a new hairstyle among young men was beginning to take hold. The flat top was an exacting cut, requiring not only special skill and extra setup effort of barbers, but also a commitment on the part of the customer to brush his hair diligently every morning to train it to stand up during the first few weeks of a new cut. Without this commitment on the customer’s end, the flat top would not set, and the barber would need to start the whole process over.

Never one to waste time and effort on a losing prospect, you made your younger flat top customers, a growing number of college students, stop into the shop every morning before classes to do their required brushing. If they didn’t show up regularly, you wouldn’t work with them anymore. Somehow it doesn’t surprise me that just about all of them showed up as ordered, and not only that, but they encouraged their friends and roommates to come to you for flat tops as well.

But this was all a bit later. In the first six months or so of your time at Sanitary Barbershop, you mostly sat on your chair and watched your co-tradesmen get all the business. You were the new guy, after all, and a kid compared to the boss and the other two. None of the regular customers knew you at first and weren’t willing to gamble their heads on an untested barber. So, they would wait for the older guys to finish up and clear a spot for them. You waited through this initial slow period. And you observed and learned how things worked around the shop: the workplace culture, the business with commissions and such, and the strengths and weaknesses of your cohorts. The experience was not lost on you. (Few of your experiences were in those days.)

Then the kids started coming in for flat tops: a trickle at first, but word spread around campus. Soon you had the whole football team. And it wasn’t long before your customer base swelled to the point that you were putting in eleven-hour days, mostly cutting and maintaining flat tops. At seventy percent commission, that wasn’t bad money. And the assurance of thirty percent of each of those many haircuts going back to the boss gave you an edge over him you didn’t have before.

Here too is where you came into your advantage: The flat top was the domain of younger barbers who had come up in training and apprenticeships during the time of its rise in popularity. Older barbers, like the guys you worked with, tended not to be familiar with the rudiments of the style, and they weren’t always willing or able to alter their course at this stage of their professional journeys. In the early fifties, you were riding the crest of the wave.

Of course, you were aware of all this and you loved it. You always had a keen sense of timing too, whether dodging a potential tackler at the last second, calling a fellow poker player on his hand, or, here, in gathering information on rivals and knowing just when and how to sock it to them.

The opportunity to sock it to your boss came by way of a young man named Murphy, who, in your own words, possessed “a beautiful head for flat tops.” With black hair and lots of it, and not the least bit curly, his was the perfect combination of factors for the new style. Compared to the curly-headed guys (whose hair you could train for flat top in a few cases, though in general it was next to impossible) and others who had the right hair but were too lazy or lacked the commitment to maintain their part in daily brushing, Murphy’s case was a breeze. It was fun.

Murphy was your customer by way of the fact that he liked to sport a flat top and you were the best one to deliver what he wanted. But it wasn’t an official arrangement. Plus, the kid wasn’t aware that he could call ahead when booking an appointment and request a specific barber. So, technically, whenever he walked into the shop, he was fair game for you or for any of your three competitors who happened to have an opening then.

You knew this about Murphy, and by this time you well understood the shop culture too. So, you took your knowledge and ran a little experiment the next time Murphy walked into the shop on a busy day and sat down in the waiting area.

“I was watching,” you said when we spoke about it in 2003:

“Murphy was sitting there, and in came some other guys. The boss, he took a guy that was almost bald headed. And he’s avoiding Murphy. I noticed the other barber—I looked at him out of the corner of my eye. He kinda looked up at the boss and didn’t say nothin’. I know that they saw each other. I was watching. He was gonna get done before me, and I slowed up a little bit more to make sure he did. And the boss didn’t give him Murphy either. He gave him another [customer]. When I got done, [the boss said] “Okay, Murphy, you can get in the chair.” So I cut his hair….”

After you finished, and Murphy left, you walked up to the boss and said, “You know, I started here a year ago, and you said I was gonna have competition. Do you remember that?”

“Yeah.”

“Well I just want to let you know I’m not stupid,” you said. “I saw you avoid Murphy, ‘cause you couldn’t cut it. And you didn’t give him to Jim, ‘cause he couldn’t cut it either. So from now on, when Murphy walks in and you’re sittin’ on your ass. You remember he waits for me.”

That day a power shift transpired at Sanitary Barbershop. From then on, the boss knew that not only was he beholden to you and your flat tops for the rise in shop revenue over the previous year, but he also knew that you were aware of it, and that you weren’t about to be pushed around by him or any of the other senior tradesmen. After that, your star rose, and you took on more leadership responsibilities. And some years later, when the boss’ health declined and he had to cut back on his presence at the shop, these responsibilities increased. After he died in the mid-sixties, you bought the business from his widow and, in 1969, you bought the building itself and collected rent from the other two units—which at that time housed a beauty shop and a lunch restaurant.

***

It was fortuitous that you were able to add landlord to your career package at this point, because the sixties most definitely affected things for the barber business, and particularly that of a barber whose niche was the flat top.

The taste of that period lingered in your craw for the rest of your life. In 2004, a full forty years after one famous episode of the Ed Sullivan show helped seal your fate as an American barber, the bitter mood behind your voice is drippingly obvious on the tape in your initial answer to my question about what cultural factors led to the decline in flat tops:

“The Beatles,” you said with mocking inflection.

But they weren’t the only culprits. According to you, the list of nefarious trendsetters included Prince Charles, whose trademark style you described simply as “long and flying all over.”

“The Kennedys didn’t help [business] any,” you added. “None of ‘em ever knew how to comb hair.”

Change can be difficult, but it’s easy to treat that phrase as an abstraction and rob it of its workaday application. Truth is, the 1960s longer hair trend cut mightily into your business, and on many levels. You may not have lost so much in terms of numbers of customers. But those customers came in less frequently as they added inches to their manes, and the tally from those lost appointments, in your estimation, added up to “the price of an Oldsmobile every year.” What’s more, flat tops all but disappeared as a hairstyle, which had to have taken a lot of the fun out of your work. Not only that but it robbed you of the distinction you shared with only one other local barber: You two were the best flat top cutters around, and together you probably did more of them than all the other city barbers combined.

By the late 1970s, many men had abandoned barbers altogether, preferring instead to patronize hairstylists in establishments commonly called (and echoed by you with deliberate ironic emphasis) “beauty shops.” Even me, your only son. I was in ninth grade when it happened, sitting in that barstool next to our kitchen, about to get a haircut from you, as I had every couple of weeks since I was little. That evening, as you prepared to start, I steeled myself and told you what I had earlier leaked to mom: that I’d been thinking of checking out a hairstylist.

Wrong topic. Holy hell, I thought you were going to kill me that night. You went into a rage that made me flee the room. You flung your clippers, and with one sweep of a hand sent the wrought-iron barstool crashing to the floor. I spent the rest of the night hiding in my bedroom. And you didn’t talk to me for days afterwards. But I kept my pledge. I went with the hairstylist and stayed. And with only one exception in the late eighties, when I was going shorthaired for a brief time and I asked you to trim up the back more, you never cut my hair again.

These days, I understand your reaction better—however out of compass and immature it might have been. Indeed, I’ve had a few of those regrettable outbursts myself as a parent. No one can hurt us like our kids can, after all.

But getting back to your reaction, I now recognize how the existential threat you felt over your loss of revenue in the years since longer hair on men became the norm had come home to you in a real and damning way when even I joined the ranks of defectors. And it wasn’t only a loss of revenue you suffered. By the 1970s, the barbershop as a ubiquitous, indeed obligatory, institution for men—a private club of sorts—was becoming a thing of the past. So, by extension, were barbers. There was a discernible decline in respect for the trade starting in the long hair era. Barbers not only came to represent the obsolete values of aging and dying generations, but they became targets for derision.

Thinking back on the period, I’ve just now recalled something that I’d forgotten: Sometime around 1974, a kid vandalized a wall sign you’d put up that pointed the way toward the back entrance to your establishment. The sign with an arrow read, “Barbershop,” but the kid had spray-painted an X over the word, “Barber” and replaced it with “Butcher.” And while I only have my mind’s eye memory to rely on these days—which, like everybody’s, is capable of error—I seem to remember the vandal had sprayed a couple of swastikas around it as well.

You laughed the nasty prank off, but still it had to hurt. Nobody would’ve called you a butcher in 1954.

***

If a silver lining can be found in the decline of barbering in the sixties and beyond, it might be that it was just this slowdown that allowed you the opportunity to ply your business brain in the pursuit of investing. Playing sports may have been your first great passion, then barbering took over through the rise and fall of the flat top. But the money-making part of your life of legend dwarfs everything.

Since you are not here to ask, I can only conjecture, but I would say with some confidence that at least some of your drive not only for financial security but financial abundance was rooted in the uncertainty and hardship you experienced as a little boy during the Great Depression. This was a time when ordinary Americans would have most keenly and intimately felt what Franklin D. Roosevelt referred to in his first inaugural address in 1933 as a “nameless, unreasoning … terror [that] paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance.”

I’m certain your family of origin was no different. By all available evidence, you never had much extra, no matter how healthy the national economy might have been at any given time. Grandma always had her hands full at home, and since Grandpa didn’t go to school past the fourth grade, his opportunities were limited to blue collar jobs and menial tasks. His occupations at various times included a car repairer for the Burlington railroad, a general maintenance man, and a shoemaker at the La Crosse Rubber Mills. In between regular jobs, he took whatever was available: house painting, harvesting watermelons, sweeping at Birnbaum’s, and putting up storm windows or screens for widows and others who needed it done. In this last type of task, you helped him, which wasn’t a bad arrangement. The two of you could get more done in a shorter time, take on more jobs, and all the proceeds stayed in the family.

From the mid-twenties through the 1930s, you all lived in a large, two-story house on Loomis Street. This was as close as Grandpa and Grandma ever came to owning property. Two women who lived down the block held the deed for the place. Grandpa paid on the mortgage, and he and Grandma took in lodgers to help with the money. But by the decade’s end, when times took another swing toward the worse in the so-called “Roosevelt recession,” the tenants no longer could pay their share in any regular way. Grandpa tried to keep them on as long as he could, hoping for a turnaround, but soon you had a bunch of renters essentially living rent-free, and no extra money coming in. By 1940, you had lost the house and had to move to an up-and-down on Rose Street, with newlyweds Genevieve and Al living upstairs, pitching in from their own job incomes to help with payments.

Things got better after the depression and World War II, though only to the degree that one was willing to put forth the effort to earn. You started out your marriage to Mom in 1948 with “two cans of Campbell Soup in the cupboard” and the certitude of your next week’s paychecks. But your work ethic was strong, nearly manic compared to most folks. I would say that, for both you and Mom, a commitment to hard work was what you valued most, not only in yourselves but in other people too. That was the crucible of merit as far as you were concerned.

And work you did. In those early years of your barber apprenticeship, you toiled for a pittance at a north-side shop and supplemented that income with frequent trips to Camp McCoy to cut servicemen’s hair. Meanwhile, Mom worked her butt off daily at the flower shop, then stopped to buy groceries before cooking supper for when you finally got back home in the evening. Sometimes, she was so tired that she’d fall asleep mid-conversation at the dinner table, and you’d lead her to bed and clean up the supper mess before retiring yourself.

You wanted kids, but for some reason were unable to make one of your own. The causal factor was never narrowed down to a single culprit, but I often wonder whether your shared obsession to establish the financial foothold that neither of your families ever attained might have stressed your reproductive potential to the point of failure.

Shortly before I came along, you did try to adopt. But Mom had bought the flower shop from her former boss by then, and the adoption folks informed you that women who were self-employed were restricted by regulation from adopting kids. This was still the era that held middle-class housewives as the ideal mother candidate, and female business owners were not among the chosen. Eventually the agencies did relax their adoption standards to include woman entrepreneurs, and they contacted you to inform you of the change. But luckily for me, after a decade and a half of trying, Mom had finally become pregnant, and you had the satisfaction of declining their overture.

I was born an only child during the spring of 1963, in the fifteenth year of your marriage.

Even though it was an impediment to adoption for a long time, the fact that Mom ran her own business offered a distinct advantage in another way: that business was wildly successful. My Florist, Inc., much like your barbershop across from a college campus, enjoyed the fortunate circumstance of proximity: It was located directly across the street from one of La Crosse’s three hospitals, and was only minutes away from most of the local funeral homes. This central location gave the shop a competitive edge, and the profits accrued to the point where, until you struck it rich in the middle 1980s, Mom was the primary breadwinner in our family. Precisely how much she made I never really knew, though, since her answer to my childish queries was always the same, delivered with typical Irish candor—namely, that it was none of my damned business.

No matter, her income was sufficient to give you some leeway in responsibility for you to dabble in investing once barbering began its slow but certain decline. Your first ventures in real estate were already underway, of course, so you’d had that early taste for speculation. The next step for you was in the purchase of stocks. You stepped into the investor role with aplomb, learning quickly as you waded into that arena. Equities investment fit perfectly with your competitive personality and the ruthlessness you’d cultivated over the years on playing fields and on the streets, with your fists. And it didn’t hurt one bit that you also possessed an innate gambler’s instinct. You were good at it, cool and shrewd. Whether it was poker, Las Vegas, or football tip boards (which you sold on the sly out of your barbershop), you nearly always came out ahead. Investing was much the same. You bought in low, watched it grow—and in some cases, split and split again. Most importantly, you had the nerve to white-knuckle your way through downswings and corrections without giving in to the urge to sell. And when you did finally sell, it was nearly always an astounding windfall. In the 1980s, you made your first coup off G. Heileman Brewing, a hometown company then making a national splash. A local business professor later told me about the day you sold your Heileman holdings at the pinnacle of their value. At the time, the man was working as a bartender at one of your hangouts. You walked in that day with a triumphant grin, slapped a check for one million dollars down on the bar, and asked him to cash it.

I can only imagine the sense of vindication you must have felt with this first real breakthrough. The guy who came up from little or nothing, setting a course for a lifelong trade in barbering only to reach your peak at the dawn of its decline; you, standing there decade after decade, cutting the hair of business executives and college professors, knowing you were as good and capable a man as any of them, but knowing too that when it came down to earning, Mom had more of a hand in it than you did. While I never heard you complain about that arrangement or ever try to stifle mom in her own ambitions, being who you were it had to ring uneasily in your mind just the same.

And much like that catch in the field at Harry Spence did for me, making that first bundle off G. Heileman Brewing propelled you into a new realm of self-belief and launched the next chapter of your own legend—one that conferred more local attention than any winning high school touchdown or masterpiece flat top could ever have done. And the wins kept coming in the 90s and early 2000s: Best Buy, Fidelity mutual funds, Berkshire Hathaway, Marshall Middleby, and more.

By the time of your death near the end of 2006, you could boast a net worth of six million dollars, and the very people who’d come to you over the years for trims and shaves—the financial planners, bankers, and life insurance executives—were now coming to you for advice.

Lovin’ it!

LikeLike

Thank you, Lita!!

LikeLike

How I remember the flat top haircuts. My two brothers and dad all sported one. Since we were pretty poor my mom cut my dad’s and he cut my brothers’. Awaiting the next chapter.

LikeLike

Thank you as always, Judy! When my son was still a boy, he acutally requested a flat top, and my dad happily obliged. This would have been in the 1990s, haha. A bit out of fashion by then. It didn’t last long.

LikeLike

Fascinating…wonder if he was my dad’s barber [we’ll never know].

LikeLiked by 1 person

Rick: Another excellent chapter. My hero and paternal grandfather got into the barber biz with zero formal training, which was the norm back in the 1910s. He ended up with his own shop where my dad swept floors, emptied spittoons, and shined shoes. When I started growing my hair in the mid 60s my mom and dad fought me tooth and nail with varying results. Grandad Carnal, who I spent a lot of time with, in and out of his shop, only ever made one comment on the issue. “If you ever want me to cut your hair, I will get you right in the chair, no waiting”. When I told my dad that, he was incensed by that (and the fact that I had no intention of taking the offer). Dad said “When I was your age, I had to wait until there was no one in the shop then (his) dad would motion me up into the chair and start trimming. If someone came in in the middle, he would shoo me out until the next lull in business. Sometimes that would not happen for several days. Meanwhile, I had to go to school with half a haircut.”

Grandad Carnal was a Roosevelt Democrat, so we referred to it as the “Hoover Depression”. Rick ________________________________

LikeLike

Thanks, Rick! Your grandad sounds like a cool fellow. I have a feeling my grandpa Brown leaned toward Roosevelt too, especially since he was a working class man and respected collective bargaining. But I don’t know that for sure. The so-called “Roosevelt Recession” I referred to occurred in the late-30s (after the initial advances of the New Deal started to peter out), and held on until the industrial mobilization spurred by the US entry into WWII. But I agree that the onset of The Great Depression had much to do with the inaction of the Hoover administration.

LikeLike