Toward Boyhood

I’ve been seeing you a lot as I’ve grown older: your eyes, looking back at me in the rearview mirror of my car. They’re my eyes, of course, but you’re there, in them, somehow. When I see those cold, blue-gray irises, they seem to embody you far more than me—so much so that I catch myself wondering what business I have having these eyes. Who am I trying to fool?

It’s a tough look. A no-nonsense, don’t-mess-with-me-or-you’ll-regret-it, stare-down look. The same calm but deadly gaze that two boxers fix on one another as the referee recites rules just before the start of a bout.

As far as I know, you never boxed. But you fought on the north-side streets plenty, from what you told me—both with local kids and, in a weekend activity you relished, against visiting farmer boys from West Salem, who you and your friends would provoke outside the Avalon dance hall.

And somewhere during all this you mastered that look.

I know this because it always worked so well on me. These are the eyes I saw and feared whenever you’d back me up against a wall during one of my infrequent, willful moments around you. From the time I was a young child, you would crowd me toe-to-toe at those times, stare me down, and crush my spirit with six words:

“Do you want to fight me?”

One shot of that look—and that loaded challenge you knew I’d never take up—would shut me down, emasculate what little outward masculinity I might’ve summoned up as a kid.

And that was precious little. At least until much later, after I learned how to fake it.

***

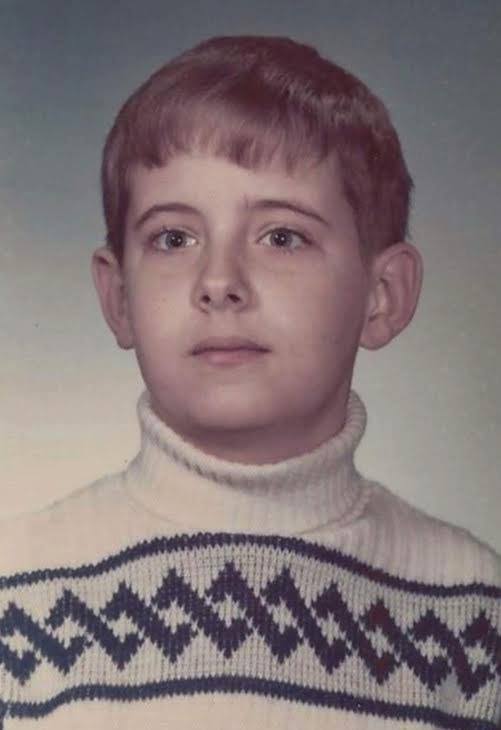

There is a school picture of me from fourth grade, 1972. My wife Katie loves the photo today, and I’ve recently grown to appreciate it more. But for years, I was embarrassed by it. Embarrassed by what I felt it suggested. I’m looking at it now: a clean-cut, brown-haired, blue-eyed boy in a white knit turtleneck sweater with a dark-blue band of intersecting zigzags across the top.

If the description stopped there it could cover the look of many kids of the era. But a study of that face tells of, or at least hints at, a deeper, more specific level of meaning. The boy, whose eyelashes are unnaturally long (pretty one might say of a girl) looks not directly at the camera, but slightly to the right and beyond it, as if lost in a particular thought he wishes he weren’t having. He’s not smiling, but he’s not evincing anger either. I used to think the subject (me) was being dismissive or superior to the cameraman and, by extension, the world. But that doesn’t fit the kid I remember. I didn’t have the ego to be haughty back then. Rather, he appears quietly resigned to something, something discomfiting that he hopes will end but he doesn’t see the possibility of it happening. His smallish mouth is a straight line, not indignant but reticent, perhaps wary of the consequences that spoken words can bring. His eyes betray innocence, interiority, and a general fear of outside forces. They appear moist, as though they could well up and spill tears at the slightest provocation.

Compared to the school pictures I’ve saved of other boys my age I look like an innocent. In their own photos, the boys I knew show eager or mischievous smiles, knowing looks, and they all exude a definite (for the time) gender-specific derring-do.

Of course, as kids we all fell somewhere along a far wider spectrum than was given credit to exist at the time, but the strictures imposed on us by stereotypes in life and media tended to pigeonhole us as either/or. A ubiquitous TV-commercial jingle laid out this narrow, and narrowing, viewpoint in unmistakable terms when it asked: “What kind of kids eat Armour hot dogs?

Fat kids, skinny kids, kids who climb on rocks / Tough kids, sissy kids, even kids with chicken pox…”

This rubric didn’t leave much wiggle room for boys, and it doesn’t seem to have considered girls at all. Analyzing my fourth-grade male self by way of it, I would have fallen by default on the skinny side since, back then, the word in kid jargon was critical, not complimentary. Back then, “skinny” was synonymous with “weakling.” Remember the Charles Atlas ads that ran in comic books and magazines for decades, where Mac, the scrawny kid, is bullied on the beach by some muscled creep and loses his girlfriend in the process? Back at home, in shame, he sends for the Atlas workout course, transforms himself into a hunk seemingly overnight. He returns to slug the bully, thus becoming the hero of the beach. The girl, suddenly impressed, gushes: “Oh, Mac! You are a real man after all!”

With that kind of social conditioning, skinny was not something one wanted to be called. But that is how I remember myself, though in truth I retained a layer of baby fat well into adolescence.

True to the hot dog jingle, I could and did climb on rocks. But compared to other boys, I was probably more likely to slip and get hurt. Plus, I would tire sooner on my way to the top. That’s because I always found myself disadvantaged whenever required to muscle my way through, up, or over an obstacle. I never could muster a single pull-up during any of the Presidential Physical Fitness Award tests each year at school. Hell, I could barely manage the girls’ version of the same exercise: the flexed-arm hang.

In general, athleticism—the very activity that made boys boys in that time—was not my thing. I could run, though never fast enough to be of any help in gym class relays. And as for team sports, forget it. My skills were so lacking that I considered it a personal triumph if I wound up being chosen second-to-last for sides.

Two games of the era that consistently proved my worthlessness as a young male were kickball and dodgeball, as both required the participant to be able to catch. As doubtless you recall, this was a skill that I lacked entirely. Sadly, it just so happened these two games were the most popular playground activities for boys—especially kickball, which meant I was in for a childhood of being consigned to covering right field. And on the odd chance that a long fly ball should enter that notoriously sleepy sector, chances were better than certain the big, reddish-brown rubber ball would pass through my arms and ricochet off my chest.

For a child who hated being called by his last name back then (it sounded demeaning to me), I sure heard it a lot during those games. “Brown!” rang the angry chorus from the infield as I’d chase the ball across the blacktop time after time, shouting apologies and bearing the weight of shame. Meanwhile, the kid who’d kicked it my way rounded the bases in glory. And there was never a chance to rectify my error by getting him out at home plate with a heroic hurl from right field to the catcher, either. My throwing ability was no better than my catching.

One incident stands out to this day, and really solidifies how I defined myself as a boy back then. It happened in fourth grade, during the brief time that I was in Cub Scouts (which I joined mainly because of the blue, quasi-military-style uniform, the shirt of which reminded me of a Union cavalryman’s getup with the accompanying yellow kerchief). After one of our weekend den meetings, we kids went to the empty playground of the Catholic grade school that was near the den mother’s house for (you guessed it) a kickball game. I was at my usual spot in the dull section of the outfield when an opponent’s booming kick came my way. I felt the dread in my gut as the ball loomed closer and closer in my sight. At what I judged the right moment, I reached up to catch and draw it into my body like I’d seen so many other boys do with apparent ease. But the ball brushed past my fingers before I could grab hold. It hit the blacktop behind me, and I watched it bounce away.

When I turned back to my teammates, the closest one to where I stood, a toothy, straw-haired kid named Glen, yelled: “Why don’t you go home where you belong, Brown. Nobody wants you here.”

So that’s just what I did. I left the game and walked the half-mile from the playground to my house in lumpy-throated silence. Later, I ate with you and Mom without saying much and went to bed early. As I lay there, I thought about Cub Scouts, my den of supposed friends, the kickball game, and Glen’s damning words.

He was right, of course. I didn’t belong there. I didn’t belong anywhere where boys are supposed to be boys. I could compete with the best of them when it came to music or books or things of the mind. And no one I knew could touch me when it came to history—Medieval England, pirates, the Civil War. But this brainy stuff didn’t matter. In the world I occupied then, being a real boy meant physical stuff: pitting your body skills against those of another boy and prevailing. And that was not even close to what I was all about.

But I was a boy, nevertheless. So, where did that leave me? What good was I, anyway? I turned to my side, hugged the spare pillow close to me, and I cried over my not belonging. I cried for the shame of my inabilities. I cried pretty much up until the time I fell asleep.

Of course, I never told you about that incident, though I now know that I could have, and that it would have been okay. You’d have probably lined me up with someone you knew at the University—a coach or physical education major who could tutor me in the rudiments of sport. Just like you did for me during kindergarten with swimming lessons. And like those swimming lessons, I’d have hated going. I’d have looked around at all the other kids with their eager, easy, boy swagger and felt like an outsider. But I would have gone anyway without vocal complaint. And it may well have changed things earlier for me.

To be honest, I probably knew then that I could’ve told you, but I would have been mortified to confess my shortcomings in athletics, obvious though they must have been. I knew how important sports were to you.

There is a baby book that you and mom had partially filled out just after I came along. It provided spaces to record my time of birth, my weight, certain other vitals. And it also included prompts to help set the temporal context. One question read, “Headline of the Day,” and written in pen on the line after it was, “Football Player of the Year is Born.” It’s unmistakably Mom’s handwriting, but I know she was dictating here. That answer was your brand of humor after all, and most certainly your hope for me from the beginning.

You and your two brothers are probably the first Browns in our line to have had their pictures printed in a newspaper. Kenneth got his in for being wounded twice in the Pacific during the Second World War. Raymond’s smiling face showed in the local paper, posthumously, the day after he drowned. And your own action-posed, steely-gaze photo appeared frequently during the fall of 1944, on the sports page, when you were a high school football star attaining local glory as a left halfback.

You also played baseball (shortstop) and basketball (forward), and excelled at both, but football was your sport of choice and the one that best suited your competitive personality and physical gifts. You liked to run, and you were fast. Locked in my memory is the oft-repeated claim that you completed the 100-yard dash in 10.2 seconds. In the early 1940s, that was moving.

You were even fast as an older man. I remember the day we were out walking in the neighborhood, like we sometimes did. Was I in ninth grade at the time? 1977? I had been gaining confidence in my own late-blooming athletic abilities then and, cocksure as a fourteen-year-old boy can be, I challenged you to a race to the fire hydrant that stood a half-block away from us. You would have been fifty then.

At the count of three, we took off.

I held the lead for the first ten yards or so, my road-gripping Adidas Roms bestowing an early advantage over your smooth-soled loafers. I must tell you I reveled in that moment—the prospect of besting you at something, anything. But your natural ability, or more probably your killer instinct to prevail, won through in the end. I heard the chuck-chuck of those leather soles coming closer as they found purchase on the asphalt surface. I glimpsed your form in my periphery at first, then watched you in forward vision as you passed me and sprinted on to win by twice the ten yards you’d yielded at the beginning.

That was the first and last time I ever challenged you in a match of physical fitness.

Nevertheless, at that time of life I was enjoying what would be the height of my involvement in organized team sports. Golden years for you, I’m sure—your boy, the athlete at last. I started as a lineman then, playing both offense and defense, on the junior high football team. In the spring, I threw discus and was good at it.

During the winter of that particular school year, though only that school year, I even joined the wrestling team, but I quit after my first two competitions, giving in to a suspicion that I lacked what it took to excel at it. In truth, I’d simply lost twice in a row and didn’t want to repeat the humiliation. I lost the first match honorably, it could be argued, after having nearly pinned my opponent in the early seconds, only to have him wiggle a leg out of bounds before the referee finished counting. In the end, he won the match on points. But my second and final wrestle, against a kid from an across-town school rival team, left me with no room to equivocate.

We took a bus to this second match in the dark of winter, hurrying into the Lincoln Junior High gym in our elastic tights and sweatshirts—a line of eager, intense teens breathing steam. I recall the bleachers being packed, mostly with the home-team crowd. When my match time came, I shook hands with the kid across from me on the mat and the referee waved the start. I planted a single step in my opponent’s direction and waited, hoping to use the same signature move I did when I almost won against that other guy the week before.

In actuality, and foolishly, it was the only move I’d ever mastered—my magic bullet. I discovered it in a technique manual that I’d bought at the one local bookstore we had back then, and one of my favorite places to be, and I studied the hell out of it: breaking the move down stage-by-stage and practicing it in slow-motion on imaginary opponents in my bedroom. It was a slick defensive maneuver in which I would use my opponent’s forward momentum against him to bring him to the mat, face down, and then use his right arm as a lever to turn him over and go for the pin. It had yielded textbook results the last time, after all, and it would surely have launched a long and successful one-move grappling career for me had the kid not thrust his foot outside the circle and messed up my aspirations.

But the new guy here at the Lincoln match was more skilled than the last one, and he clearly knew a hell of a lot more than one move, because before I could even think he had me on by back from a single-leg takedown. Wrapped up in a cradle hold with one leg in the air like the outstretched arm of a miserable supplicant, I was helpless. All I could do was smell the kid’s harsh, garlicky breath as the ref counted to three, and to listen as the crowd roared its approval over my patent and very public downfall. Lying there, pinned, I remember thinking this was probably the last thing a gladiator in the Coliseum heard as the emperor’s thumb went down and the opponent’s sword finished him off. And while I’m not certain, I’d wager this had to have been the quickest match of the 1977-78 season, and for all I know the quickest and most decisive in the history of both schools.

Back in our own locker room later that night, I informed my coach that I wouldn’t be continuing in the sport. He didn’t try to talk me out of it.

***

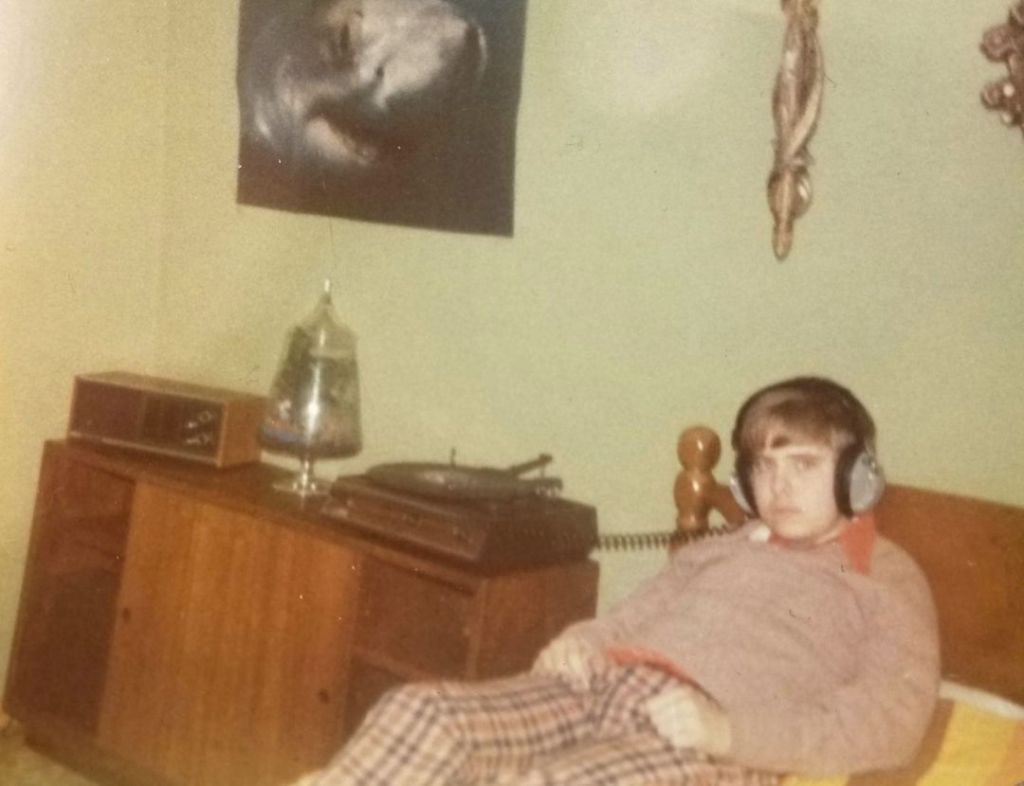

Despite my brief and undistinguished wrestling venture, I had by this time developed a real love for organized sports. From around seventh grade until my sophomore year, when I would exchange my cleats for a bass guitar and a pot pipe, I devoured sports-related reading material: biographies of great athletes, books on technique. I began lifting weights in our basement during junior high—to the accompaniment of the radio, playing the hits of the day like “New Kid in Town,” “Lonely Boy,” and others. All these labors and preparations paid off in results.

But this is getting ahead of a larger story that began with a lucky break in the spring of 1975, at the end of my sixth-grade year. A short while before then, you’d bought me a baseball fielder’s glove from the downtown J.C. Penney, probably so I could join in the games around the neighborhood, maybe pick up some boyish skills along the way. It wasn’t a fancy and more expensive Rawlings or Spalding model. I don’t recall it being a name brand glove at all. For all I know, it was a J.C. Penney store issue.

But that glove was amazing. Not at first, of course. At first it was like any new glove: stiff and unforgiving, hard to press shut, hard to catch with. And this is the shape it was still in on the afternoon that a group of us at Harry Spence organized a softball game during recess. It was the bottom of the final inning (which meant, in practical terms, that the bell ending recess was about to ring), and my team was ahead by one point. The opposing team was up, and they had two outs and a fast boy on first base.

I was standing in right field with my new glove when I heard the “tink” of an aluminum bat making contact, and suddenly a pop fly was coming my way! Oh no, I thought (and I’m sure every kid on my team echoed the sentiment). The fast kid on first was already nearing second and was sure to score in the time it would take me to chase down a missed ball and throw it to someone closer to home.

Now, the smart and confident athlete would have watched the ball from the very beginning, knowing (and relishing) that he was to be the deciding factor between victory and defeat for his team—the fate of many in his hands. He would have judged the rise and fall and calculated the approximate place where the ball would come to land—and position himself directly under it with glove and reserve hand raised to meet and snatch it from space for the out.

But that wasn’t my strategy. My plan (in fact my entire sports involvement up to that point in my life) was to stand in right field or some equally useless spot and pray that nothing would come my way, and thus be able to avoid the rebuke of my teammates when (never if) an error on my part should prove disastrous. The last thing I expected or wanted was a game-deciding fly ball to mess with my athletic anonymity.

But here it came, and it was a floater. What’s more, I could now see it was bound to fall somewhere far in front of where I stood. It would have been one thing to miss a solidly-hit fly because it soared far beyond my position and kept rolling with its great momentum—the sandlot equivalent of an out of the park home run. Nothing a kid can do about that: the batter was just a slugger—like Hank Aaron or Harmon Killebrew. But this one was a high pop, now in free fall and within my compass of responsibility. I had no choice but to make a try at catching it, despite the disadvantage of my late start at getting under it.

It’s hard to recall whether I felt fear or not. Given my history with fielding I should have been quaking in my Converse tennies. To this day, I don’t know what propelled me. All I can say today is it must have been a moment of unwitting, one-pointed meditation, something like Kwai Chang Caine might’ve experienced on the “Kung Fu” TV series. But I bolted toward the spot where I needed to be, lunged forward with my left arm and J.C. Penney glove outstretched. The ball dropped dead into the pocket, and I squeezed the glove shut around it.

Batter out.

Just then, too, the school bell rang. Game over.

I stood in shock afterward, gauging the weight of that softball still trapped in my glove. A caught ball in my glove. The next thing I’m aware of is the cheering of my teammates. I’d made the winning catch! They’re tossing their own gloves into the air in celebration, running up to me, patting me on the back and lauding me for my catch.

It was the first time in my life I had ever been praised for a sports accomplishment.

Until the day comes when my brain seizes up and no longer permits me to recall things, this moment in the grassy field outside of Harry Spence Elementary will stand as a pinnacle. It is no act of hubris to claim that it changed my life. It did. For one thing, at the basic level I now knew it was possible for me to catch balls. What’s more (and I had proof), I could do so at critical moments. My participation made, and could in the future make, a difference. And if I wanted to extrapolate from there into the realm of life, the feat suggested that I really could do just about anything I set my mind to.

The catch even altered my fantasy thinking. Before this, in my daydream I’d always imagined myself as a consul in the Roman republic or a general on the field of battle—something that started after seeing TV movies of ancient conflict like “Cleopatra,” and those depicting modern warfare too, like “Patton”—which you and mom took me to see at the Twin Cities’ Cooper Theater during my second-grade year of school.

My long-term goal back then, at least in my dreams, was nothing short of world conquest and its attendant glory. Psychiatrists would’ve had a field day with me: the inward life of a consummate attention seeker. I even had my cabinet of ministers chosen ahead of time, and they included my favorite recording artist of the time, Gordon Lightfoot, who of course would be the overseer of music.

But from the time of the catch and into the near future, my fantasies of grandeur changed in focus. No longer was I the armored Roman consul or an emperor of a conquered planet. Now I was a sports star. And my first dream of glory in this guise was set on that very field outside Harry Spence Elementary. In it, I was a batter who had never previously gotten a hit—a vision not too far off the mark in real life at the time.

My fantasies often had a soundtrack, maybe something classical, or perhaps the tunes of Gordon Lightfoot or Elton John played on my bedroom record player. During a crescendo in a chosen song, I’d imagine the pitch coming my way. And at the pinnacle I’d swing, meeting the ball and launching a slugger-worthy, bases-loaded-home run fly ball to center.

As the ball bounced somewhere in the very farthest reaches of the outfield, I’d round the bases in glory, just behind my three teammates. But then, as my own foot touched home plate and everybody on my side gathered around me to praise my accomplishment, I’d be struck by an attack of some sort and fall dead at their feet, and my teammates would be left to mourn my tragic passing and, most importantly, to regret that they had ever doubted my ability to perform in a clinch.

Aside from this melodramatic death scenario (which began a years-long string of post-mortem fantasies in which people who had somehow wronged me come to regret, albeit too late, the error of their ways), the only sad thing about the real-life catch I made in sixth grade is that I don’t recall having ever told you about it. Surely, I must have. Hearing it would have pleased you immensely, and thus would have pleased me in turn.

Indeed, in what I now recognize as my codependent way of thinking, knowing that you knew about it and approved of my performance would have been nothing short of life affirming. Your reaction is a memory I would have treasured, yet I’m conjuring nothing right now about having shared the news. I suppose it’s possible I kept the information from you because a part of me suspected the catch had been a fluke. Or maybe I held it as a private triumph to be savored alone. (I rather doubt this last possibility; that is a stage of enlightened development I still haven’t attained.) Somehow or another, I would have conveyed the news to you.

But why do I not remember doing so?

No matter, I guess. At least I know that the change in my attitude and drive after that catch was apparent going forward, because I began to work hard to be not only competent, but good at sports. This new behavior was conspicuous, and completely at odds with all that had gone on before, and this alone must have given you hope for my future as a boy on his way toward manhood.

As for that glove, it was to have a stellar career, at least in terms of neighborhood games. You taught me all about caring for it: rubbing in Neatsfoot Oil to nourish the leather and improve flexibility, placing a ball in it during off-season storage and wrapping the glove tight with rubber bands to create a fitted pocket. I tell you, flyballs just dropped into that glove over the ensuing years! I didn’t even have to try to catch them. Sure, part of it was the hours of practice I put in: tossing the ball onto the pitched roof of our house to imitate the unpredictable drop of a flyball. And, of course, the hundreds of hours spent with the neighborhood kids, playing catch and softball games at the park at the end of our block.

But to this day, I think some weird kind of energy infused that J.C. Penney glove the instant I made my first catch in sixth grade. No other way to explain it. That thing became magic. So, in a way, did I.

I can smell the Neatsfoot Oil.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Smells like America.

LikeLike

Wow, I am loving this. Your descriptions are so detailed. I can feel my glove in my hand again. I miss those days so much

LikeLike

Thank you so very much, Patty! Your comment means the world to me. And I get it–I often miss those days too. The world seems so much more complicated these days. But I guess every generation says words to that effect at a certain stage of life…

LikeLike

I can relate to not being athletic even though I am a female. In grade school I was always last to be picked for a team and I was on the chunky side so not a fast runner either. I too was interested in reading. In high school I found out I loved roller skating and learned to dance on skates at the rink on the northside. The only time in my life that I felt graceful! i think my dad would have been around the same age as your dad. I am 80.

LikeLike

Thank you so much for both reading this and commenting, Judy! My dad would be 95 if he were alive. He and my mom were married 15 years before they had me in 1963. So you grew up on the northside?

LikeLike

No I grew up on the southside living most of my life on Greenbay St.. Married my husband Bob Wood who lived about a block away on the same street. I am 80 and he is 81. I attended Holy Trinity School and Aquinas graduating in 1960 (before you were born). My husband attended Longfellow and Central graduating in 1959. We started dating in 1958 and hit the big 60th this November.

LikeLiked by 1 person

So good!! Your writing places me in your moments. Your reflections calm, soothe, and they are very relatable.

LikeLike

Thank you, Chey! I’m always blessed to hear from you. Be well, dear friend.

LikeLike